Black historian, Carter G. Woodson, established the celebration of black history in 1926. Originally observed as a week-long event uplifting the contributions of Black Americans, for Black Americans–it was the hope of Dr. Woodson that one day all Americans would recognize the contributions of black people as an integral part of U.S. history.

As a kid I didn’t celebrate Black history month in my predominantly white elementary school. Nor did I learn an awful lot about the accomplishments of Black Americans. My earliest recollection of the mention of black people in history, came from my 2nd grade teacher. She was a young, white educator that I really liked. I remember sitting up in my seat as she opened a book about Abraham Lincoln. As she began to tell the children’s version of honest Abe’s legacy, she looked directly at me with a smile saying, “Lincoln freed the slaves.” The end. Mind you, I was the only black child in the class and one of the few black children in the entire school. I, along with all my white schoolmates were reminded of my black skin difference. As all eyes turned towards me, I felt ashamed to have been singled out for my blackness. This version of the story of slavery minimized, devalued and dehumanized my black identity and the truth of slavery– while centering whiteness as powerful and the norm. That is what racism does—it sustains a racial hierarchy that privileges those with white skin, while simultaneously denying the inherent worth, power and dignity of people of color.

Today, the adult version of me does not blame the lack of knowledge of a young, white educator so many years ago, but the damage caused in that moment plagued me for years. In my spirit, I knew she was wrong, but I did not know how to respond it hat moment. I had no rebuttal to her nonexistent narrative of the civilizations, history, and gifts of people from the continent of Africa; or the true horrors of the transatlantic slave trade; or the courage of freedom fighter Harriett Tubman that sought freedom from bondage for her people. Slavery was just a footnote in history.

To counter what I didn’t learn at school, my parents and grandparents taught me my history around the dinner table, at family gatherings and in the black church. Raised under Jim Crow segregation, my parents were not ashamed of who they were; nor where they came from. Works of black artist were proudly displayed in our home. We listened to the soulful sounds of WKND AM radio station that provided a platform for black artists, musicians and producers—when white radio would not. We traveled south each summer from Connecticut to Mississippi and Alabama visiting the childhood homes of our parents. We learned the National Negro anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” and sang the lyrics to “We Shall Overcome” at my grandparents’ church. Black publications, Ebony, Jet and Black Enterprise magazine littered our coffee table with images of black athletes, beauty queens of the Historic Black Colleges and Universities, celebrities, scientist, political figures and entrepreneurs. We attended theater performances of all black play productions. Dolls of every shade and hue filled my bedroom bookcase. We watched Alex Haley’s Roots as a family and purchased the album soundtrack produced by composer Quincy Jones. For me, Black history wasn’t only an event during the shortest month of the year—it was our way of life. The power of celebrating Black history (and all history of People of Color) contradicts the racial stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination imposed on People of Color by a white dominant culture. Valuing one’s own racial identity, ancestry and history is part of the necessary healing work of ending racism.

Reclaiming history…

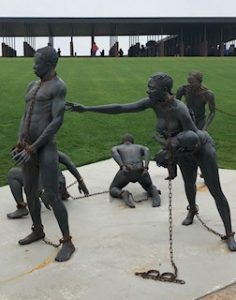

On August 23-25, 2019 people around the world will remember the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in North America. This event will mark the Quad-Centennial of the forced transatlantic voyage of enslaved African peoples to Virginia. On August 25, 1619, a pirated ship carrying stolen human cargo from Africa arrived in the English colony in North America. Taken from the Angola region of Africa, these men and women were known for their agricultural, metal working and farming skills. These skills would prove to be invaluable and profitable for the survival of English colonist. The arrival of this first slave ship set in motion the transatlantic slave trade. From the 16th to the 19th century between 10 million and 12 million African people were kidnapped, enslaved and scattered throughout the Americas. Slavery and the Middle Passage was an event of monumental proportion that not just affected North America but changed Africa forever. The legacy of racism and fear of people of African descent are rooted in the policies, practices, beliefs and actions that legalized slavery, legitimized the slave trade and colonialism. Four hundred years later, the descendants of the transatlantic slave trade still face racial barriers in affordable housing, voting, employment, education and health care. “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”– Maya Angelou Connecting the dots of the transatlantic slave trade, the forced removal and assimilation of Native American Indians; the denial of citizenship of Chinese workers and the exploitation of migrant Mexican farm workers are all crimes against humanity in American history. We cannot change history or its impact on past generations, but it is important to know and teach the truth of this history.

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America is partner of the organization Bread for the World’s “Lament and Hope”: A Pan-African Devotional Guide Commemorating the 2019 Quad-Centennial of the Forced Transatlantic Voyage of Enslaved African Peoples to Jamestown, Virginia (USA). The devotional makes the connections between Bread for the World’s mission to end hunger and the history of the enslavement of African descent people; the creation of racialized policies within the U.S and the colonization on the continent of Africa. As a collective Christian voice, Bread for the World further recognizes and acknowledges the role many churches have played in supporting and perpetuating these horrific practices and policies. In 2019 at the Churchwide Assembly, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America will issue an apology for slavery to People of African Descent.

The downloadable devotional resource is available at bread.org

Sculpture featured at the National Memorial For Peace and Justice, Montgomery, Alabama.

Judith E.B. Roberts, serves as Program Director for Racial Justice.