by Giovana Oaxaca, Program Director for Migration Policy

The allegations of medical neglect and invasive gynecological procedures in a privately-run detention center in Irwin County, Ocilla, Ga.—including coerced sterilization—quickly drew disbelief and condemnation worldwide this fall. Far from unique, these shocking allegations echo the historic and current reality of cruel and inhumane treatment towards migrant women. At every stage and step of their lives, migrants, immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers are at special risk of having their fundamental human rights violated.

GBV as a migration driver

What drives people to migrate will vary from person to person, but one of the most cited reasons is to escape from domestic abuse and violence. For countless women, girls, and LGTBQIA+ persons in the Northern Triangle of Central America–El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—sexual- and gender-based violence (GBV) is inescapable reality. Every day, over 100 cases of violence against women are filed in Guatemala. In 2018, a woman was killed in Honduras every 18 hours. El Salvador has the highest rate of femicide in Latin America and in an 8-month span of time in 2020 at the height of pandemic quarantine measures, reported 84 femicides. Globally, gender-based violence is widely recognized as a key human rights issue, as highlighted in the international 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence campaign.

What drives people to migrate will vary from person to person, but one of the most cited reasons is to escape from domestic abuse and violence. For countless women, girls, and LGTBQIA+ persons in the Northern Triangle of Central America–El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—sexual- and gender-based violence (GBV) is inescapable reality. Every day, over 100 cases of violence against women are filed in Guatemala. In 2018, a woman was killed in Honduras every 18 hours. El Salvador has the highest rate of femicide in Latin America and in an 8-month span of time in 2020 at the height of pandemic quarantine measures, reported 84 femicides. Globally, gender-based violence is widely recognized as a key human rights issue, as highlighted in the international 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence campaign.

Even these figures likely do not capture the full scope of the violence experienced by women. Social stigma, fear of retribution and lack of confidence in authorities often contribute to underreporting.

Shifts in U.S. Policy Toward Asylum Seekers

The United States has a policy of granting limited humanitarian protections to persons fleeing gender-based persecution and violence. Unfortunately, overtime, these protections have become harder to access. Under President Trump, the U.S. government has undermined protections for people fleeing domestic abuse and gang violence and turned away asylum seekers, trapping families, men, women and children in precarious conditions without any meaningful access to protection. People at risk of GBV thus contend with persecution at home, in transit, and even from U.S. authorities.

ELCA responds to human need

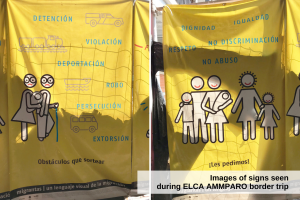

While working with migrating, returned and deported women, civil society organizations and faith-partners have expressed the need for services geared at empowering women socially, politically and economically. The ELCA’s AMMPARO strategy (Accompanying Migrant Minors with Protection, Advocacy, Representation and Opportunities) has placed a special emphasis on working with advocates in Central America who give witness to these perilous conditions and supported their advocacy efforts.

“Migrants, immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers often suffer more when they are women, girls, or gender non-conforming people” notes the ELCA social statement Faith, Sexism, and Justice: A Call to Action.” “Women, girls, and people who identify as non-binary must not be deprived of their human or civil rights.” When the disturbing account of human rights violations against immigrant women in custody of the privately run Irwin County Detention Center surfaced, ELCA Presiding Bishop Elizabeth Eaton stated, “As the ELCA we strongly condemn gender-based violence and violations of human rights wherever they occur.”

Threats in U.S. detention

Abuse of women is widespread in immigration detention centers and constitutes a serious threat to the civil and personal liberties of migrants. The detained population has multiplied over the last 30 years under a U.S. government policy to apprehend and detain increasing numbers of immigrants. Alternatives such as community-based alternatives to detention, although humane, less costly and more effective, have not been pursued, overburdening an already strained system at the expense of the people detained.

The United Nation High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) guidance says that all immigration practices should implement special measures to protect women from sexual and gender-based violence and exploitation in detention. According to the UNHCR, other groups that are vulnerable to abuse, like children and members of the LGBTQIA+ community, should also be afforded special measures to guarantee their safety. The UNHCR mainly advocates that detention should be used as a measure of last resort and asylum seekers should be given every opportunity to seek protection. The U.S. government must do more to meet even this basic standard of care.

In fact, the U.S. federal government has become one of the most egregious perpetrators and accessories of GBV. Between 2010 and 2017, there was a staggering 1,224 complaints of sexual assault abuse in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention yet only 43 investigations. Based upon known patterns, these numbers likely reflect underreporting. We know people don’t come forward out of fear of retaliation and are not consistently supported by confidence in prosecution of perpetrators. Like most cases of GBV, these acts are committed in nearly total impunity.

What can we do?

Increased scrutiny at Irwin creates new incentives for advocacy

- Supporting policies that aim to curb profiting from people’s suffering are one way to stamp out immigration practices in the U.S. that deprive women of their liberty and rights.

- Restoring the asylum system so that victims have access to humanitarian protections goes without saying—though the underlying definition of gender-based asylum could stand to be improved.

- Supporting survivors of violence at the onset through advocacy in their home countries, so that they do not feel obligated to flee, must also be an objective of any strategy to prevent and mitigate acts of GBV. The escalation of intimate partner violence, evidenced by the spike in femicides in El Salvador, signals the need to expand local programs for women in need of protection in their homes.

- The Keeping Women and Girls Safe from the Start Act of 2020 (S. 4003) includes some important measures to expand the U.S. government’s ability to prevent gender-based violence and provide early interventions at the onset of humanitarian emergencies.

These are just a few examples of systemic and institutional changes that can be made, and they are very likely to take some time to come to be implemented. However, these lay the groundwork for a just and compassionate solution to the unacceptable reality of sexual- and gender-based violence.