‘Wild’ Places

I have been interested in environmental activism, indigenous justice, and decolonization since I was a kid (I was a nerdy and revolutionary child, what can I say?). It became apparent over the course of my time in college and grad school. During my MDiv/MA program, I took a class on Environmental Law and Policy. One of the professors engaged us in a discussion about the early days of environmental policy and the focus on the US’ imagination about wilderness and the Muir-inspired notion of preserving ‘wild’ places.

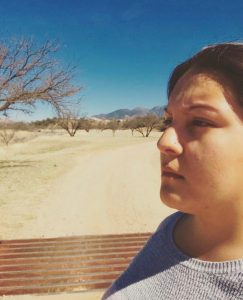

Taina on a walk on the grounds of Santa Rita Abbey in Patagonia, AZ- the traditional land of the Hohokam, Sobaipuri, Ópata, Tohono O’odham, and O’odham Jeweḍ peoples- on a trip for a class entitled, “Ecotones of the Spirit.” She writes “we spent time with tribal communities and other organizations working towards sustainable/indigenous food systems and immigrant justice on the border. I felt the spirit of the land, inspiring me to take this photo.” March 2017.

Somehow (it was me, I did it) the conversation became about the fact that “wilderness” doesn’t exist. Indigenous peoples have been engaging with, traveling over, and altering the surface of the Earth since before European arrival; the ‘noble savage’ cliché in popular imagination came about because the white settlers didn’t perceive changes Native people made to the environment. Because there were no brick buildings, churches, gravel roads, or vehicles, the alterations were invisible to their eyes.

Indigenous Land Intervention

There are many cases of ecosystems suffering from the absence of indigenous intervention, including the increasing frequency and intensity of forest fires and wildfires in California. The reason? Climate change, sure. But until recently, the Chumash and other California tribes were prohibited from performing controlled burns of accumulating debris on the forest floor as their ancestors did for generations.

Plain in Patagonia, AZ

My explanation receives confused looks from the class, and a dismissive comment from my professor. “I’m unaware of any policy implemented to prevent such interactions, and I don’t know about that history.” I’m certain he wasn’t trying to be rude. He’s a cool guy and I respect him, but it continues to bother me that someone with so much education and experience in environmental law would perpetuate the colonizer narrative about ‘wilderness.’ At the same time, it’s not surprising considering his racial and socioeconomic status.

Reclaiming Rejected History

It’s important for me to converse with white folks about the reality of rewritten or rejected history by colonizers and how that affects what they believe about indigenous peoples and land use. One of my goals is decolonizing educational spaces and reclaiming history as part of the work of environmental justice- working to ensure communities of color and other historically oppressed communities’ health and well-being are no longer ignored or put in harm’s way through the creation or implementation of environmental regulations.

Christian Relationship to Creation

Christianity has a lot to answer for in this regard, and therefore Christians should be involved in seeking environmental justice alongside indigenous peoples. The historic Christian propaganda of “Manifest Destiny,” based in the Doctrine of Discovery (a papal document declaring Christian Europeans’ divine right to seize land from non-Christian Natives via killing, enslaving, and/or converting them) came about because of the white colonial conceptualization of “wilderness.”

Engaging Creation on a hike in Hanging Rock State Park in NC on the traditional lands of the Saura and Tutelo people. 2017.

Historic efforts to tame the North American wilderness resulted in suppression of traditional ecological knowledge and practices. Many Indigenous communities are working to reclaim their sovereignty and their ancestral relationship with the land. Christians can learn from the traditional conceptualization of relationship with the land, and there are notable efforts by theologians to do so. A Christian theological ethic that incorporates our relationality with Creation into our spiritual imagination could turn us from the colonial idea of “wilderness” to understanding ourselves as part of a sacred community.

I pray that the practice of #NoPlasticsForLent brings us to a place of reflection, repentance for the perpetuation of colonialism, and prayer for environmental and racial justice. Amen.

Reflection / Discussion Questions:

1) What are some environmental justice issues that you are passionate about? How does your faith inform how you respond to these issues?

2) What spiritual practices have helped deepen your relationship with creation in the past? What practices might you let go of / adopt this Lent?

3) Who are Indigenous leaders in your community? How might you follow their lead in relationship to Creation? How might you learn more / support their work going forward?

4) Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin? Then your light shall break forth like the dawn, and your healing shall spring up quickly; your vindicator shall go before you, the glory of the Lord shall be your rear guard. Then you shall call, and the Lord will answer; you shall cry for help, and he will say, here I am. (Isaiah 58:6-7)

What are your favorite justice-oriented verses of sections of Scripture? What about verses describing Creation?

If you’re unsure, check out ELCA Advocacy resources for inspiration! https://www.elca.org/Resources/Advocacy#CongregationStudies

Taina Diaz-Reyes is the 2020-2021 Hunger Advocacy Fellow with ELCA Advocacy’s DC office. A “Lutheracostal” originally from Tucson, AZ but raised in the DC area, she graduated in 2016 from George Washington University with a BA in Geography and Sustainability, then completed the MDiv/MA in Sustainability dual degree program at Wake Forest University in December 2019. Passionate about using geographic and decolonizing research methods to pursue social and environmental justice, her background includes research in environmental quality and management, the role of science in society and politics, indigenous food sovereignty movements, racial justice, food justice, and decolonization. Her hope is to do doctoral research and theologically informed advocacy to pursue a more sustainable human connection to the Earth and each other through research and writing on food and faith.