Our garden at home has finally started yielding its bounty, which means we have more tomatoes than we know what to do with and are engaged in constant battle with rabbits to preserve our harvest. Now is the season when we get to enjoy the fruits of our time spent planting and preparing the soil, with fresh bites from the garden in every meal. It’s a reminder of the growing season and of nature’s wonders.

The fresh veggies making their way from my yard to my plate has had me thinking more about community gardens recently, especially with the rising costs of food making harvests more important for many of us. Interestingly, though, it was not my own garden or food prices that made me look into the history of gardens in the United States. It was, of all things, a comic book.

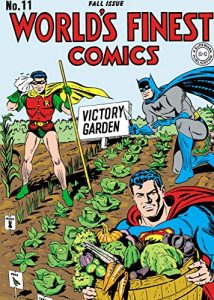

Most people who know me know that I am obsessed with comics, especially propaganda comics from World War II and early 1950s horror comics that drew the ire of parents and the federal government alike. I recently picked up a copy of this little gem from 1943:

World’s Finest Comics is pretty unremarkable, except for its run of war-themed covers in the early 1940s. Issue #11 here features Superman, Batman and Robin working away in a “victory garden.” (Oh, how nice it would be to have the super-speed of Superman or the ingenuity of Batman to take care of weeding and tilling, right?) Victory gardens, as they were called, were home gardens that the US government encouraged people to start during the war, ostensibly to increase food production at home when so much produce had to be sent to troops overseas, though their significance went far deeper, as we will learn below.

Many people trace community gardens today back to these victory gardens. But the community gardening movement actually started much further back, and the government was not as “super”-supportive of victory gardens as Superman and Batman were – at least early on.

The 1890s – Community Gardens Begin

According to Smithsonian Gardens, part of the Smithsonian Institution, community gardens trace their roots back to Detroit, Michigan, in the 1890s. The economic depression of 1893 hit the city hard, particularly affecting its largely immigrant population. Worried about food shortages and high unemployment, Detroit’s progressive Mayor Hazen Pingree started a public works program for jobs and then encouraged the city to use vacant lots to grow vegetables for the coming winter. “Pingree’s Potato Patches,” as they were called were called, were effective and popular.

Mayor Pingree had another motive besides providing food. The depression had increased economic inequality in the city, and the response of Detroit’s wealthy citizens was to provide charity to address the deep challenges faced by the workers most impacted. Rather than addressing the problems, charity drives fostered a system of patronage, leaving low-income Detroiters dependent on small amounts of help from rich benefactors. Pingree’s gardens were steps toward a more equitable solution, providing spaces for Detroiters facing hunger and poverty to exercise agency. It was a movement for both food security and economic justice. As the Detroit Free Press wrote in 1935, “Pingree’s potato patches broke the back of hunger. They were nationally acclaimed and copied. They revealed a city of boundless energy and industry unwilling to live on doles (the meager charity of the wealthy).”

A family tends a Pingree Potato Patch in Detroit. Image courtesy of the Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Turn of the Century and World War I

Pingree’s model was copied in many major cities. As the depression eased, schools turned to gardens both to supplement nutrition and to help an increasingly urban population of children connect back to nature and learn responsibility and the value of work. Perhaps the most famous advocate for the school garden movement was Fannie Griscom Parsons, a tireless leader whose work led to the creation of gardens and farms for children throughout New York City in the first two decades of the 20th Century. Parsons famously wrote,

I did not start a garden simply to grow a few vegetables and flowers. The garden was used as a means to teach [children] in their work some necessary civic virtues; private care of public property, economy, honesty, application, concentration, self-government, civic pride, justice, the dignity of labor, and the love of nature by opening to their minds the little we know of her mysteries, more wonderful than any fairy tale.

With World War I, the gardening movement gained a lot of ground and new support, this time from the US War Gardening Commission. With this fervor, the Commission reported that by 1917, there were more than 3.5 million war gardens across the country, helping supply needed fruits and vegetables during the lean years of the war.

As should be clear by now, though, the gardens were about more than just food. The war gardens of World War I became a symbol of community agency and renewal, especially for African American residents, whose urban neighborhoods were neglected by governments after the war. Drawing on their horticultural skills and passion for beautifying their communities, African American gardeners in Detroit, Philadelphia and other cities scaled up their post-war efforts, even holding contests for residents with the best gardens. These gardens became an important lifeline during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

World War II – Victory Gardens

The World War I gardens planted the seed (ahem) for the victory gardens of World War II. By this point in agricultural history in the US, the government was more reluctant to support gardens. As the Smithsonian notes, most officials thought that large-scale agriculture was more effective. What ultimately convinced the government to promote victory gardens, though, wasn’t a compelling argument about production. Rather, it was the awareness after decades of use that gardens play a powerful role in bringing communities together, improving relationships between neighbors and strengthening morale.

The gardens ended up proving effective in both areas, though. They strengthened communities and they provided an abundance of food – as much as 40 percent of vegetables grown in the US by 1944.

Hidden Depths

The brightly-colored produce, however, hid some gnarled roots, and Superman, Batman and Robin’s smiling faces on the cover of World’s Finest Comics #11 belied deep injustices when it came to gardens and farms in the United States in the 1940s.

As World War II began, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal and internment of Japanese Americans. While in public press, the order was motivated by fear of spies (a belief that had no basis in reality), the internment campaign had more sinister roots. Japanese Americans, especially in California, had drawn on their deep agricultural knowledge to build successful farming businesses upon their arrival in the US. It was these farms, and the valuable land that Japanese Americans owned, that drove some to call for internment.

Indeed, one of the first documented lobbying efforts to remove Japanese Americans from the West Coast came from none other than the Salinas Valley Vegetable Grower-Shipper Association, which sent a lobbyist to Washington, DC, to argue for forced removal of Japanese American farmers.

By 1942, with Japanese Americans interned and their land under government supervision, white farmers began seizing control of their farms, and the managing secretary of the Western Growers Protective Association reported “considerable profits were realized” by member growers “because of the Japanese removal.”

While incarcerated at the internment camps, many Japanese Americans continued using their skills, however, and developed camp gardens. Despite the desolate landscape of many of the camps, internees used their wisdom, creativity and tenacity to start thousands of thriving gardens. These gardens helped to supplement their diet, but perhaps more importantly, the gardens served as a symbol of resistance against internment, an attempt to hold on to community and traditions and to refuse the dehumanization of internment.

Gardens that had once been indicators of successful business and wealth for immigrant families now, through acts of protest against the injustice of internment, were revealed as symbols of courage, strength and resilience.

Sowing and Reaping

Still today, community gardens carry these multiple layers of meaning. On the one hand, they provide fresh, healthy food. But on a much deeper level, as researchers Rina Ghose and Margaret Pettygrove report, community gardens are spaces where community is formed and citizenship is fostered. They are a protest against powers that control food, land and jobs. And they can be spaces that bear witness to new kinds of communities, new kinds of relationships and new understandings of the economy.

Martin Luther once wrote that farming is an act that imitates God’s creation of the world. By digging into the soil, planting and nurturing crops, we are imitating God’s hands-on approach to making the world. But the long history of gardens in the United States – from immigrants tending “Pingree’s Potato Patches” to investments in gardens for under-served urban children to beautification of segregated neighborhoods and the witness of camp gardens – points to an expanded understanding of how this work imitates God’s creative endeavors.

Yes, we are gifted with the opportunity to witness the Creator God in action as crops take root, but on a deeper level, the community that is nurtured and grown at the garden testifies to the ongoing work of God as the redeemer of the world, reconciling us to one another and building a just world where all are fed.

We aren’t superheroes, but we don’t need to be. The world does not need superheroes as much as it needs neighbors willing to work together, to participate in the restoration of just relationships and communities, asserting together that our neighborhoods are worth investing in and that each and every one of us can play a part. As we’ve learned time and again, gardens can be sacred spaces where neighbors build relationships with one another, assert their pride and dignity, and create a bountiful harvest for the community to enjoy. The hard work of tilling, planting, weeding and watering yields far more than vegetables. It can nourish the growth of communities in profound, life-giving ways.

As we harvest from gardens this season and get ready for planting next spring, this history begs the questions: what are we really sowing? And what new wonders might neighbors working together for the transformation of the landscape and the community reap?

If you are interested in starting your own community garden, or finding new ways to expand the garden your community has, check out ELCA World Hunger’s Community Gardens How-To Guide, available in English and Spanish! You can order hard copies from the ELCA World Hunger resources page too!

Ryan P. Cumming, Ph.D., is the program director of hunger education for ELCA World Hunger.