“Sweet dreams.”Uttered almost like an extension of bedtime prayers, whispered and spoken with a gentleness intended to comfort, these two words invoking the gift, “sweet dreams.”

In 1963 on a national stage, a 35-year-old Martin Luther King, Jr. was about to take his seat when Mahalia Jackson urged him go further. “Tell them about the dream. Tell them.” Two months prior to his historic sermon at the march on Washington, Dr. King had spoken passionately begun to speak of his dream for our country. It was in Detroit that King began to echo the refrain, “I have a dream.”

It is the perspective of some, looking back, that Dr. King was not sure about sharing, there in Washington, the outline of what the dream called for. Without the urging of Mahalia Jackson, “tell them about the dream” what has been heralded as one of, if not King’s most memorable sermons, would have ended quite differently.

Dr. King reminded those gathered for the Great March on Detroit in 1963, that we were standing about a hundred years from the Emancipation Proclamation, dismantling of legalized enslavement of Africans in the United States. King lamented that one hundred years later the Negro in America was still not free, “But now more than ever before, America is forced to grapple with this problem, for the shape of the world today does not afford us the luxury of an anemic democracy. The price that this nation must pay for the continued oppression and exploitation of the Negro or any other minority group is the price of its own destruction. For the hour is late. The clock of destiny is ticking out, and we must act now before it is too late.”

There are many who now remember very little of Dr. King’s historic sermon beyond, “I have a dream.” In that sermon, both in Detroit and in Washington, he spoke of an urgency that was demanding that we as a nation move with intent and purpose, and an energy “an anemic democracy” could not and cannot render.

In the three years that followed, Dr. King, his messages and the movement became clearly more unaccepting of any notion of gradualism. His writings from a Birmingham jail were gathered to become the basis of his book under the title “Why We Can’t Wait.”

As he spoke more openly about the intersectionality of poverty and the pattern of poor people being pitted against one another by the manipulative hands of empire, the more he lost favor with European Americans who had once at least claimed to be allies. King’s speaking against the global injustices of war and poverty were met by powerful voices insisting that he stay in his lane.

In 1967 in an interview with NBC news correspondent Sander Vanocur, Dr. King spoke of the dream he preached about in 1963 now becoming in many ways a nightmare. By 1968 when he ventured into the hostility of Memphis Tennessee to stand in solidarity with striking sanitation workers, he spoke not so much about the dream but resolutely about “the difficult days ahead.” Surely it remains even more evident that “we cannot afford the luxury of an anemic democracy.” We are well within the challenge of the difficult days King envisioned, that demand of us more than superficial notions of cross cultural relations and justice only on the terms of brutal empire.

Our beloved prophetic drum major never abandoned the sweet dream.

Action Item

April 4, 2018 marks 50 years since Reverend Dr Martin Luther King was assassinated. The National Council of Churches, an umbrella organization of mainline Protestant, historic black and Orthodox denominations, is leading “Act Now! United to End Racism.” People of faith will come together on April 4th to commit to realizing Dr. King’s dream to resolve to end racism. Events include an April 3 ecumenical service at a Greek Orthodox cathedral, an interfaith prayer service and rally on the National Mall on April 4, and a lobby day on Capitol Hill on April 5. Visit the National Council of Churches Facebook page to learn more : https://www.facebook.com/nationalcouncilofchurches/.

Bio

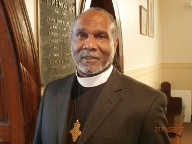

In August 2014, Pastor Starr began work as ELCA Director for Ethnic Specific, Multicultural Ministries and Racial Justice Team of the ELCA–after serving as Director for African Descent Ministries since 2009. As a pastor /teacher he takes great delight and special joy in helping to lift up and engage the gifts and talents of people of African descent and others, celebrating their capacity for building a stronger church and a better world to the glory of God through Jesus Christ. He was awarded an honorary doctor of divinity degree from Trinity Lutheran Seminary in Columbus Ohio. Pastor Starr and his wife Judith have two adult children and two grandchildren. He is the first of seven children born to Albert and Eunice Starr of Durham, N.C.