Today’s post is from Krehl Stringer, pastor at New Salem Lutheran in Turtle River, MN. This is the second in a series on why and how to initiate celebrating a Season of Creation in worship.

A good place to begin planning a Season of Creation is with a 4-, 5-, or 6-week series of lectionary readings—there are a variety of 3-year lectionaries to choose from. The period from September 1 (the beginning of “Creation Time” in the Eastern Orthodox tradition) to October 4 (the Feast of St. Francis in the Roman Catholic (western) tradition) has become the ecumenical standard for introducing a Season of Creation into the church year. Local conditions, however, may indicate a better timeframe, or a congregation might select individual Sundays throughout the year. Themes on Sundays during creation time draw worshipers’ attention to various domains or aspects of creation (e.g., planet earth, wilderness, humanity, river, and world communion). At New Salem we have also added in an “Advocacy Sunday” each year to amplify particular callings for eco-justice (e.g., Fire/Energy Stewardship, Food/Water Security, and Sustainability).

A good place to begin planning a Season of Creation is with a 4-, 5-, or 6-week series of lectionary readings—there are a variety of 3-year lectionaries to choose from. The period from September 1 (the beginning of “Creation Time” in the Eastern Orthodox tradition) to October 4 (the Feast of St. Francis in the Roman Catholic (western) tradition) has become the ecumenical standard for introducing a Season of Creation into the church year. Local conditions, however, may indicate a better timeframe, or a congregation might select individual Sundays throughout the year. Themes on Sundays during creation time draw worshipers’ attention to various domains or aspects of creation (e.g., planet earth, wilderness, humanity, river, and world communion). At New Salem we have also added in an “Advocacy Sunday” each year to amplify particular callings for eco-justice (e.g., Fire/Energy Stewardship, Food/Water Security, and Sustainability).

There are many places online to access free worship resources for planning a Season of Creation. To start, check out Lutherans Restoring Creation, Let All Creation Praise , and Season of Creation. Calls to worship, hymns, blessings, lectionaries, preaching commentaries, prayers, artwork, videos, and much more will ignite that spark of creativity in pastors and other worship planners to invite all of creation into worship and praise of God the Creator, Healer, and Sustainer of life.

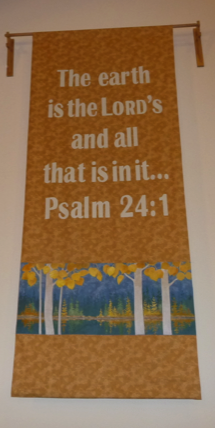

Interspersed throughout this blogpost are several pictures from churches where we have celebrated a Season of Creation. The idea is that a congregation would get to know the environment in which they have been planted, then develop a multi-faceted Season of Creation that reflects the local character of that context. For example, in northern Minnesota in the fall, the tamarack trees burst into a bright golden yellow. So our church adopted tamarack yellow as the color for our Season of Creation; paraments, stoles, and banners were beautifully crafted. The night sky of rural northern Minnesota is spectacular, so during the week of Cosmos Sunday, we hosted a couple star parties open to the public. The Saturday before Fauna Sunday, we held an annual Blessing of the Animals ceremony. One year, we invited parishioners to contribute to a progressive  Season of Creation Art Gallery that by the end of the season had photos, paintings, sculpture, fiber arts, and mixed-media on display. Special guests were often invited to preach or give a presentation after worship on various themes; opportunities were promoted for learning more about community supported agriculture, local recycling programs, political lobbying efforts, bird watching, prayer hikes, and so much more.

Season of Creation Art Gallery that by the end of the season had photos, paintings, sculpture, fiber arts, and mixed-media on display. Special guests were often invited to preach or give a presentation after worship on various themes; opportunities were promoted for learning more about community supported agriculture, local recycling programs, political lobbying efforts, bird watching, prayer hikes, and so much more.

For any congregation, engaging a Season of Creation can be a profoundly revitalizing (and exciting!) experience for all generations in discovering how, “in Christ, there is a new creation [to explore and celebrate]: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new!” (2Cor. 5:17)

It would be a great joy for me to hear from you your stories of celebrating a Season of Creation in your place of worship. You can reach me by email at lightstringer2@gmail.com.

Good Shepherd Lutheran Church is nestled in the heart of Vermont’s Green Mountains in the small city of Rutland. Just downhill from ski areas like Killington and Pico, and a short drive from beautiful glacial lakes and the southern reaches of Lake Champlain, this picturesque community is surrounded by forest, farms and an array of wildlife. I like to imagine that it’s not that different from the hilly region that Francis of Assisi called home when he was called to rejuvenate the Church.

Good Shepherd Lutheran Church is nestled in the heart of Vermont’s Green Mountains in the small city of Rutland. Just downhill from ski areas like Killington and Pico, and a short drive from beautiful glacial lakes and the southern reaches of Lake Champlain, this picturesque community is surrounded by forest, farms and an array of wildlife. I like to imagine that it’s not that different from the hilly region that Francis of Assisi called home when he was called to rejuvenate the Church.

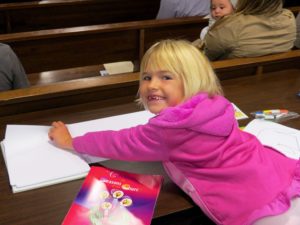

This summer we took out a couple of pews in the back of church, long wooden benches that are designed for fifty minute sitting sessions. We replaced the pews with coloring tables. They were an immediate hit. No signs were needed as to why the tables were there. Their presence just said WELCOME to a certain segment of the communion of saints.

This summer we took out a couple of pews in the back of church, long wooden benches that are designed for fifty minute sitting sessions. We replaced the pews with coloring tables. They were an immediate hit. No signs were needed as to why the tables were there. Their presence just said WELCOME to a certain segment of the communion of saints.