Today’s post is written by Chad Fothergill. Chad serves as cantor to the Lutheran Summer Music community, is editor of the Association of Lutheran Church Musicians journal CrossAccent, and is author of Sing with All the People of God: A Handbook for Church Musicians.

How silently, how silently the wondrous gift is giv’n!

So God imparts to human hearts the blessings of his heav’n.

No ear may hear his coming; but, in this world of sin,

where meek souls will receive him, still the dear Christ enters in.

(ELW 279, st. 3)

Throughout the past several weeks, posts about Advent and Christmas planning have begun to appear on social media forums for worship leaders. Like conversations about Holy Week and Easter during the pandemic’s onset, these prompts and discussions ask important questions: What will these seasons look or sound like this year? How will liturgical practices and local customs adapt to essential measures—masking, distancing, abstention from singing, and more—that slow the spread of a deadly respiratory virus, the long-term effects of which still remain unknown?

As a cantor, I’ve read such conversations with a mixture of interest and exasperation. There is much creativity in our midst, and many are faithfully planning with appropriate responsibility and care.

And yet, some appear reluctant to abstain from practices that, for the sake of our neighbors’ wellbeing, need to be shelved for a season. As my spouse, a physician, recently wrote, it is imperative that we distinguish between “wants” and “needs” during these uncertain times. A wise colleague keenly observed that many persist in attempting “to continue producing the same products at the same rate on the same scale, despite their drastically changed contexts and circumstances.” Although treasured rituals may provide solace and comfort, perhaps especially at Christmas, attempts to preserve or project “normalcy” are, at this time, fraught with peril—not only physical dangers from the virus, but distractions from the church’s mission to serve a world in need. For many communities, such “normalcy” continues to perpetuate poverty, unequal access to health care, and unjust treatment before the law. Wringing our hands over aesthetic choices risks ignoring those deprived of basic choices.

As we have learned these past months, the pandemic compels us to rethink patterns and assumptions, the abundance and amenities that we take for granted. We have heard stories of care and empathy alongside episodes of selfishness and greed. Though tragic, the pandemic invites us to think more carefully and intentionally about Christmas, to peel away crusty accumulations of nostalgia so that we might find deeper meaning in the temporary absence of brassy spectacle or candlelit ritual.

The first Christmas was a small gathering and probably not so quaint, especially when one imagines the realities of birthing an infant in a lowly stable (ELW 269). An angel choir announced the news not to wealthy elites, but to poor shepherds in their fields. The birth of Jesus was politically significant for people awaiting fulfillment of God’s promise after centuries of imperial abuse. As two noted scholars have summarized, most of those empires “behaved as empires do, with their attendant oppression, injustice, and violence.” According to Matthew’s gospel, news of Jesus’s birth ultimately sent the despotic Herod into a murderous fit of rage; his fragile, paranoid ego and naked thirst for power led to widespread death and destruction.

Advent and Christmas invite us, like Mary and Elizabeth, to ponder mystery (ELW 258), to embrace the plain and understated, and expect God to turn the world around (ELW 723). Christmas is not contingent on our lighting candles while beloved carols are hummed or sung by a soloist. Christmas is not contingent on seasonal cantatas or choral music, even small-scale works for a few voices. Perhaps it will suffice to let the angels in Luke’s gospel serve as your choir this year? Christmas is not contingent on the sentiment or nostalgia evoked by the sights, sounds, and trappings that seek to package, market, and commercialize it.

We don’t always need to reenact Jesus’s birth with a pageant, but we often need to refresh our understanding of incarnation, covenant, gift, hospitality, humility, and other keywords of the Christmas story. How does your community attend to those who have no room at the inn? Assist those for whom silent nights are impossible because of unemployment, food insecurity, or domestic violence? Care for neglected children? Comfort those whose nights are too silent during times of grief and loss?

And yes, we need assembly encouragement for these things—to hear powerful Advent prophecies proclaimed in our midst, to sing the Magnificat, to pray. I, too, yearn for the return of physically gathered assemblies that breathe and sing together. And I realize the importance of Christmas liturgies (or any liturgy) for those enduring separation, isolation, or grief. Technology has facilitated powerful preaching and proclamation, praying, and music making during these months—neither are those to be discounted!

But, in this time and place, I think there are more pressing concerns than how to light candles while physically distanced or schedule services like a liturgical version of Ticketmaster. Could funds for battery-operated candles be instead diverted to a local shelter or food bank? Instead of worrying about streaming licenses for the King’s College version of that favorite carol, could we devote time to teaching its stanzas and melody so that families can sing at home, even play just the melody on an instrument? Can you help provide access to hymnals—even if borrowed from the church—to facilitate singing at home?

Like the paschal cycle—Lent, Holy Week, and the fifty days of Eastertide—there are many ways to bring rituals of the incarnation cycle—Advent, Nativity, time after Epiphany—into the home: Advent wreaths and evergreen adornments, Advent calendars with a word or song for each day, trimming and blessing a tree for the twelve days of Christmastide, baking together, and blessing the home on Epiphany with a marking over the main door (20 C+ M+ B+ 21). Many of these and more are described in resources such as Sundays and Seasons, as well as in Gertrud Mueller Nelson’s wonderful book To Dance with God: Family Ritual and Community Celebration. Many congregations are exploring how to deliver items to their worshiping community for use in the home; such gift boxes serve as tangible reminders that we are still connected as the body of Christ. Consider sending an Advent devotional or family activity cards. The Taking Faith Home resource from Milestone Ministries offers additional ways families can connect the Sunday lectionary texts to our life together. If households do not have access to a hymnal, these could be loaned or purchased. Candles or materials for simple craft activities could also be included.

During these months, silent and empty sanctuaries have reminded us that the church is not confined to buildings. Before us is an invitation to do more teaching, to set aside the what and how of liturgical logistics and focus instead on the why of it all. While worship planning requires careful attention to a variety of contexts, may we also direct our thinking toward these larger concerns and to our neighbors, and be open to the blessings, challenges, and lessons that follow.

Come, Lord Jesus!

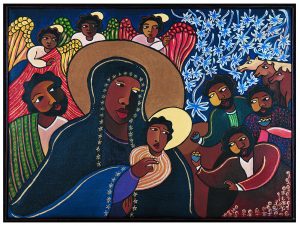

Artwork by Laura James. Nativity, 1996 (c) Laura James. Used with permission. laurajamesart.com