Nearly 500 years ago, the young monk Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to a church door in Wittenberg, Germany, and kicked off the movement that would become the Protestant Reformation. The theological disputes that followed have been well-documented over the centuries, but what the Reformation meant for the church’s witness in the midst of hunger and poverty is often forgotten. In this series leading up to October 31, 2017, we will take a deeper look at the Reformation’s importance for the church’s social ministry – and the important work to which people of faith are called by the gospel.

Throughout the week, we’ll look at different quotes, counting down to the 500th Anniversary. Today, we have an oft-neglected barb from Luther’s 95 Theses:

#9 – Thesis #45 – “Christians are to be taught that he who sees a needy man and passes him by, yet gives his money for indulgences, does not buy papal indulgences but God’s wrath.”

Yep, Luther was big on God’s wrath. Sin and its penalties were very concrete for Christians in Luther’s day, and he was no exception. In fact, it was this fear of God’s wrath that contributed to Luther’s excessive use of the Catholic sacrament of confession, much to the reported annoyance of some his confessors. On the other hand, one can scarcely imagine the freedom Luther felt when confronted by grace. I like to think that some of his brutal passion against the Church was in defense of other poor souls who, like him, had lived in fear of a vengeful God.

But that doesn’t stop Luther from invoking God’s fiery anger when convenient, especially when it comes to church practices that he viewed as theologically incorrect and harmful. Indulgences were at the top of his early list.

What Does This Mean?

An indulgence was, essentially, a certificate that reduced the time one had to spend in purgatory before entering heaven. These weren’t a new development in Luther’s day but had been around for quite some time. One of the earliest reports of indulgences was in 1099, when Pope Urban II granted indulgences to the soldiers who traveled to the Holy Land as part of the Crusades. In their original form, indulgences reduced the amount of penance a sinner had to do to cleanse themselves from sin. They were granted most often to Catholics who had done some great service for the Church.

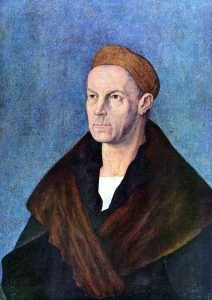

But in Luther’s day, the practice of indulgences took a dark turn, in large part to a man named Albrecht (check him out there on the left.) Albrecht became an elector (sort of a combination of bishop and political ruler) of Mainz in Germany. There were costs associated with this promotion, though, and Albrecht had to take out a loan to pay for vestments and other things appropriate for his new seat (and, one can imagine, a pretty righteous potluck for guests at the celebration of his appointment.) Albrecht took out a loan from a powerful banking family called the Fuggers.

But in Luther’s day, the practice of indulgences took a dark turn, in large part to a man named Albrecht (check him out there on the left.) Albrecht became an elector (sort of a combination of bishop and political ruler) of Mainz in Germany. There were costs associated with this promotion, though, and Albrecht had to take out a loan to pay for vestments and other things appropriate for his new seat (and, one can imagine, a pretty righteous potluck for guests at the celebration of his appointment.) Albrecht took out a loan from a powerful banking family called the Fuggers.

The Fuggers were, perhaps, one of the wealthiest families in history. They had holdings throughout Europe and the Middle East, and everyone from the Pope to the Emperor was in debt to them. Greg Steinmetz has argued that it was no coincidence that in 1515, Pope Leo X “revised” the Catholic Church’s teaching on usury, allowing for the first time in Christian history the collection of interest on loans. Pope Leo himself was a beneficiary of the Fuggers’ practices.

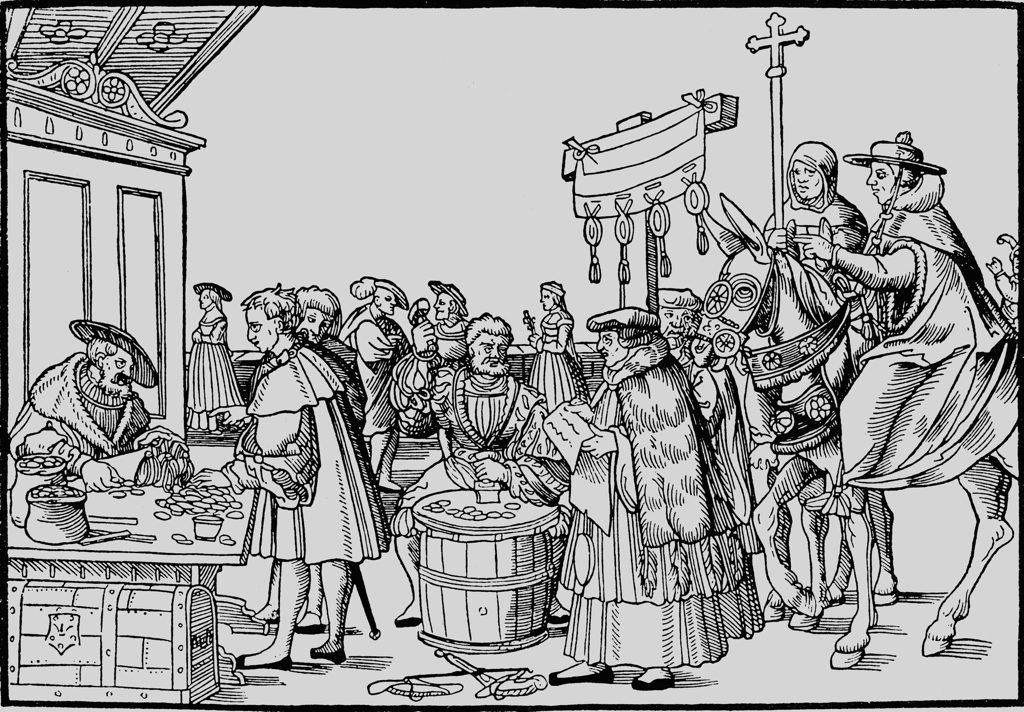

Anyway, back to Albrecht. So, Albrecht needed money, and if you needed money, you went to the Fuggers. (That’s Jakob Fugger in the painting below.) This came with hefty interest payments, though, which means Albrecht needed more money to pay back the loans. Enter: indulgences. Albrecht employed a salesman named Johan Tetzel to travel throughout Europe selling these indulgences as a way of paying back his loan, all the while promising buyers that they or their recently departed loved ones would spend less time in purgatory as a result. Pope Leo X, no stranger to extravagant spending, also engaged in the trade, using indulgences to raise money to build St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Luther, like many of his contemporaries, knew what was going on. He saw poor peasants spending money on indulgences rather than on feeding their families. (Which was understandable. Why feed your child today, if you could buy their eternal salvation for all their tomorrows?) He also saw wealthy people flinging money at indulgences instead of using their largesse to support their neighbors in need. At the same time, he came to understand the truth of justification by grace, the belief that humans can not earn – or purchase – their own salvation. Salvation, Luther saw in scripture, was and always would be a gift of God, not a reward from the Pope. Finally, enough was enough, and Luther posted his 95 Theses – formally titled Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences – and kicked off the Reformation.

The theological reasons behind Luther’s opposition to indulgences are more familiar to most. But what has been muted in history are the economic complaints Luther had against the system. Here was the church, defrauding (in Luther’s mind) poor peasants out of their meager earnings in order to line the pockets of wealthy cardinals, popes, and the bankers to whom they were indebted. He also saw the church encouraging people to throw their money at building grand cathedrals while their neighbors starved. Luther saw bad theology being used to justify greed, all at the expense of people in need.

So What?

As much as we focus on the important notions of “grace alone,” “faith alone,” and others in this Reformation Anniversary season, it’s important to remember that Luther was driven not just by a desire for more scripturally-attuned theology, but also by the exploitation bad theology made possible. It makes one wonder, where today might we hear “theology” masquerading as a cover for greed or exploitation?

Part of the heritage of the Reformation is the belief that true theology – theology that authentically reflects the witness of scripture – is theology that calls people of faith to meet the needs of their neighbors, inasmuch as God desires the well-being of all. Ironically, then, if we want to discern whether our theology reflects God revealed in scripture, perhaps one good test might be asking, “How does my theology affect my neighbor? Does it encourage service of my neighbor? Or, does it justify their exploitation?” This is the flip-side of Luther’s 95 Theses. Indulgences were not merely a theological, theoretical problem. They were a social problem that enriched the few while impoverishing the many. If our theology does the same, perhaps it is time for another Reformation.