This post comes from ELCA World Hunger’s weekly email list, “Sermon Starters.” For this week, Rev. Angela Khabeb of Holy Trinity Church in Minneapolis, shares with us her reflections on forgiveness and how we are called to make this gift more than an act, but a lifestyle as followers in Christ.

If you’d like to receive posts like these ahead of the liturgical calendar, please subscribe to ELCA World Hunger Sermon Starters by clicking on the link, or email us at hunger@elca.org.

Here is a recent review of the resource from Vernita Kennan of the Saint Paul Area Synod:

“I receive the ELCA World Hunger Sermon Starters each week from the ELCA and find it is a helpful way for me to look ahead and “preach my own sermon” in preparation of what I will hear next Sunday at my home church, Incarnation Lutheran…You needn’t be a rostered person in the ELCA to find them inspirational.”

February 24, 2019 – Seventh Sunday after Epiphany

Luke 6:27-38

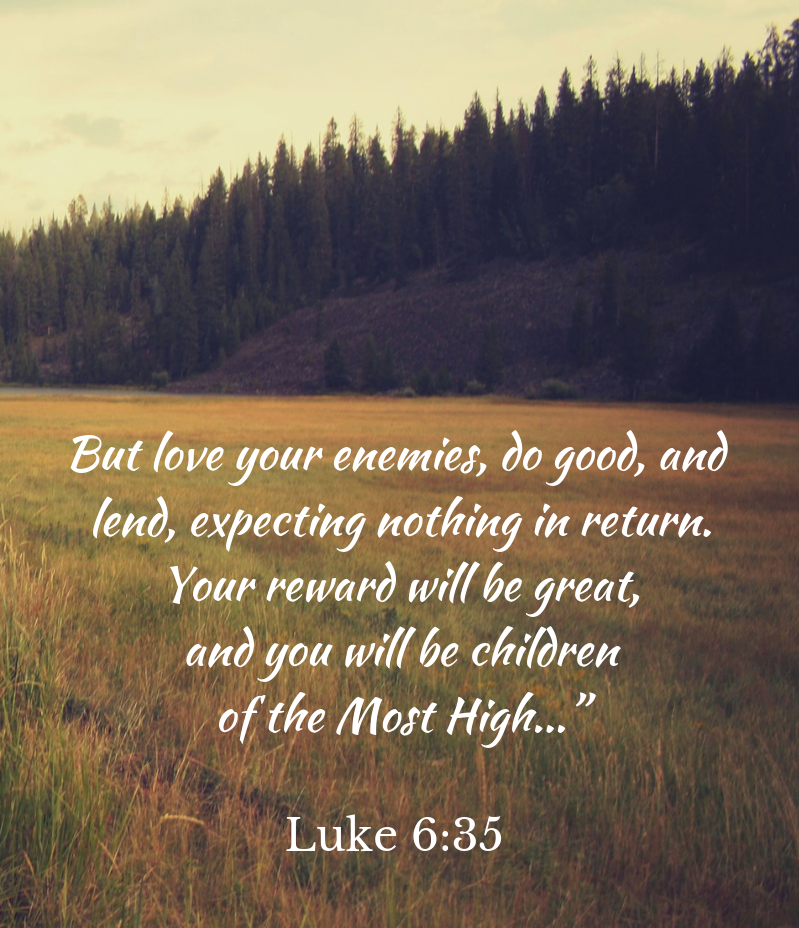

We continue this week with the Sermon on the Plain. We hear Jesus proclaiming a new way. “Turn the other cheek, go the second mile, love your enemies.” Unfortunately, this passage has been misused in some religious circles.

Please allow me this commercial break…

If someone is in an abusive situation, they are not required to stay and risk their life and/or the lives of their children. There are times when it is best to forgive from a distance. We can continue to love the person but if the relationship is physically, verbally, emotionally, or economically abusive, the most loving and faith-filled response we can have is to practice self-care. When we try to enforce forgiveness like it is a law and not an act of God’s love and grace, all of humanity is in jeopardy.

We’ve heard these passages many times before. But for the original hearers, these words were earth-shattering. Jesus’ words were radical. More to the point, his life was radical. After all, Jesus constantly challenged the status quo. He repeatedly broadened the center so that those on the margins of society would be included. He challenged the religious leaders of the day and caused so much political upheaval that he received the death penalty.

Jesus was revolutionary in ways that people never expected. Even today, Jesus enters our lives in unexpected ways and I love it. After all, Christianity should not be comfortable for us. The Gospel should not be like our favorite pair of jeans or a pair of old shoes or a worn-out sweater that we drag out this time of year. Certainly, we find comfort in God’s word. But we don’t need to have a hold on the Gospel because Jesus does not belong to us. Rather, the Gospel needs to have a hold on us because we belong to Jesus. Otherwise we are just nominal Christians playing church. We create our own brand of Jesus that suits our needs and pets our egos. We manipulate Jesus into whatever makes us feel safe, or superior, or righteous. So, what is the earth-shattering news we need to hear?

You see, the life changing power of the Gospel message has the greatest impact on our lives when it is destabilizing. Whenever we are challenged to redefine or examine who we understand Jesus to be, we grow. Whenever we challenge what it means to be a Christian in our world today, we grow.

In the Sermon on the Plain, Jesus is encouraging his followers to abandon business as usual. Through his sermon, Jesus turns the accepted societal norms inside-out. This is Good News because even when we dishonor God by our actions or inactions, God still seeks after us. Now, for the life of me I cannot figure out why. But Jesus chooses to use us as the salt of the earth and the light of the world. Jesus chooses us even though we are broken, selfish, and woefully imperfect. Jesus chooses us to broaden the center in our own communities so that all God’s people have a seat at the table. Jesus uses us to increase God’s healing and hope in the world. Is this the earth-shattering news for us?

Genesis 45:3-11, 15

It’s hard to ignore the theme of forgiveness in this week’s lessons—and believe me, I tried. Yes, the story of Joseph is a powerful illustration of love and forgiveness overcoming hatred and bitterness. But even as I encounter this undeniable witness to the hidden hand of God, I find myself distracted by many questions.

Firstly, what does true forgiveness look like for us? What happens to trust? Is it wise for me to trust this person again if they had deliberately betrayed me? What if the best I can do is just be cordial to them? Isn’t that enough? Isn’t it enough for me to simply not hate the sight of them? Let’s face it, forgiveness is hard. There’s no “forgiveness switch” on our hearts that we can simply click on or off when we need more or less of it. I’ve been wondering if forgiveness is like love. You know, when you give away love it multiplies and comes back to you.

Sometimes it seems, in our country, we are more concerned with punishment than we are with peace. We seem more concerned with revenge than reconciliation. We find it easier to fight than to forgive. No wonder some of us find it difficult to accept God’s extravagant gift of love. Even when we are receptive to God’s mercy and forgiveness, we may yet be reluctant to give mercy and forgiveness to others. Maybe we feel that we are giving away our power when we forgive. Maybe we are simply afraid of being hurt again and use our grudges to keep us safe. But, at the end of the day, ministry involves risk.

It can feel like a risk to forgive. But what exactly are we risking? Our power, position, politics, morals, self-constructed ideas of who we are and how others should perceive us seem to be potential risk-factors to forgiveness. But on the other side of forgiveness, on the other side of the tension and resistance we often experience when confronted with someone who has “wronged” us, we find relationship. We find a leveling and sharing of power, we find mutual respect and dignity, and we find the Holy ground that lives between us all. If hunger and poverty are symptoms of deeply broken relationships around the world, forgiveness could be our first-step on the path to living lives of abundance and sharing.

Forgiveness is not necessarily an event, but rather a lifestyle. God doesn’t expect us to forgive perfectly every time. But God is encouraging us to live our lives with forgiveness as our North Star. In doing so, we honor God and we help heal the body of Christ. C.S. Lewis illustrates forgiveness as part of our baptismal identity as Christians:

“To be a Christian means to forgive the inexcusable because God has forgiven the inexcusable in you.”

This is both gift and challenge.

To be clear, forgiveness cannot erase pain or eliminate the need for justice. But forgiveness is God’s gift to us. The Holy Spirit empowers us to share that gift with others. Fortunately, forgiveness, like most things, gets easier with practice. The more we remain open to the Spirit, the more able we are to forgive. Forgiveness can be extremely difficult, but it is possible. In fact, God makes all things possible for us. This is good news.

Children Sermon

Forgiveness seems to be an overarching theme in this week’s lessons. Forgiveness is an important concept that might be difficult for children to grasp. We learn to say we’re sorry but that does not always lead to forgiveness. Have you ever heard a child offer an angry “sorry!” because her mother told her she had to apologize? It happens with my kids on occasion.

So, it might be a good idea to ask the children to help you describe forgiveness. This way you can gauge the understanding of the group. Invite the children to share examples of times when they needed to receive forgiveness or times when they needed to forgive someone (be prepared to share your own examples if need be).

For an object lesson, bring two items–something rather heavy and something rather light. A brick and a feather would work well and pretty easy to get. Grudges are heavy like this brick (or rock or concrete paver–probably less than $1 at your local hardware store). Forgiveness is light like this feather (or cotton ball or stuffing from a pillow). You could get a sturdy backpack and put several heavy objects in it and invite a child or two to try and carry it. Ask who would rather carry the heavy bag or the cotton ball all day.

Remind them of the words about forgiveness in the Lord’s Prayer. Say it out loud, “Forgive us our sins as we forgive those who sin against us.” Encourage the children (and adults) to listen for those words later in worship. Remind them that Jesus helps us forgive and forgiveness brings joy.