For many of our neighbors, the economic consequences of the pandemic has thrust them into the sometimes-confusing world of applications, documentation and eligibility requirements that make up our public assistance programs here in the United States. The federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) increased funding and broadened eligibility to many of these programs, but since many of these programs are administered by states, how to apply depends on where you live.

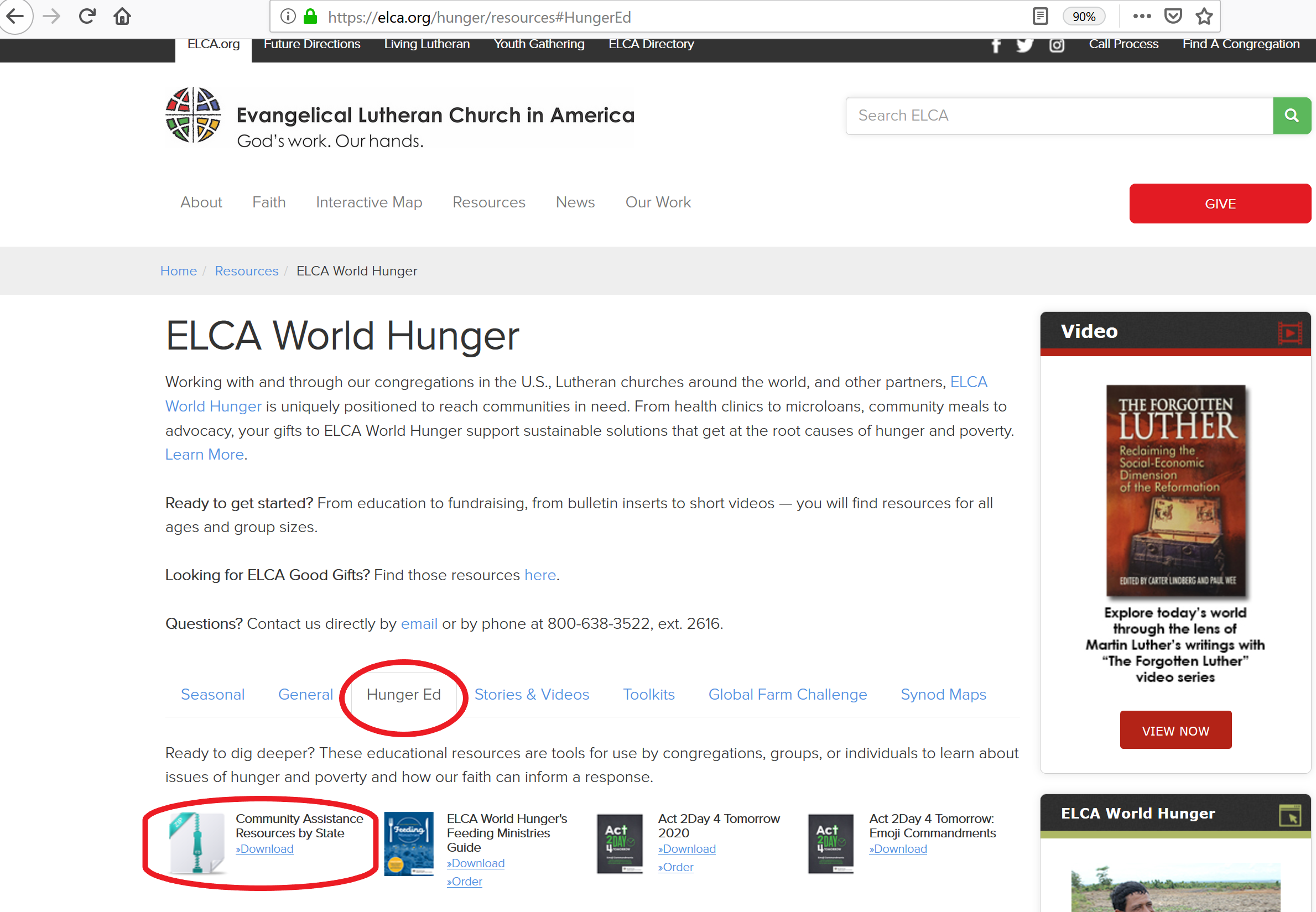

ELCA World Hunger’s newest set of guides, “Community Assistance Resources by State,” is meant to help potential applicants get started in applying for benefits they and their families may need. Each one-page guide has links to information and applications for each of the following programs for all 50 states and Washington, DC:

- unemployment insurance;

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP);

- Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC);

- Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP);

- Rental and housing resources from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD); and

- child care assistance (for most states).

In addition, each sheet has contact information for the National Suicide Hotline, the National Domestic Violence Hotline and the Farmer Crisis Hotline.

We included some information about changes to programs, where possible, though with many programs in flux, we only included information that we are reasonably certain will still be accurate as we head into Fall 2020.

How to Use the Community Assistance Guides

The guides are on the ELCA World Hunger resources page under the “Hunger Ed” tab. All of the states are grouped together in a zip folder. If using a PC, simply save the folder to your desktop, right-click on the folder once it is downloaded and click “Extract All…” A folder with all of the guides should appear.

The guides are on the ELCA World Hunger resources page under the “Hunger Ed” tab. All of the states are grouped together in a zip folder. If using a PC, simply save the folder to your desktop, right-click on the folder once it is downloaded and click “Extract All…” A folder with all of the guides should appear.

The guides are meant to be a starting point for finding applications and information on public programs. These can be shared electronically with members of a congregation, contacts on an email list or with clients of a feeding ministry. They can also be printed and placed in bags with food during distribution days at a food pantry. These can also be posted to social media groups for a community or shared on a website.

As you can see in the Montana guide above, most of the information contains links to websites, while some also have phone numbers. There are a few reasons for this. First, the agencies that administer many of these programs have been overwhelmed with calls. Some potential applicants are finding that hold times are very, very long, if their call is answered at all. Going online is typically the quickest way to apply. Where possible, we included links to paper applications for some assistance programs, for folks with challenges filling out forms online, either due to internet access or ability level. The second reason is that the most up-to-date information on eligibility and process can be found online.

Having direct links to the information can also help potential applicants find what they need much faster. Digging through state government websites can be tricky, and there are several websites that appear to be state-run are not the right sites and may present a risk for security of applicants’ information. The links on ELCA World Hunger’s Community Assistance Resource Guides have been checked by multiple staff for accuracy.

What If Clients Don’t Have Internet Access?

The COVID-19 pandemic is revealing what many folks have known for years: there is a deep digital divide between communities that have access to the internet at home and communities that have insufficient or no access. So, how can neighbors who don’t have internet access use these resources?

There are a couple solutions to this problem. First, some of the guides have links to paper applications that can be printed out and sent to congregation members or placed in a bag of food during distribution at a food pantry. The paper applications usually include the mailing address for the agency, so this is one easy solution.

Second, if your ministry has switched to a drive-through or walk-up model at a church, look into how far your church’s wifi extends on the property. For some churches, guests may be able to access the network from their cars. Consider setting up a waiting section of the parking lot for guests to access the church’s wifi and fill out the application using their own computers. In many cases, the applications are quick to fill out. This does depend on your state, though. For unemployment insurance, some states have set up scheduled days when applicants can apply. Be sure to check these first. Also, be sure to check with the church administrator to make sure the wifi connection is secure and available for clients to use.

Another option during food distribution is to provide computer stations outside for clients to use. This is a bit more difficult. The computers would need to be secure (especially in deleting browser history after each use), socially distant from other computers, guests, or volunteers, and covered in such a way that they can be easily disinfected after each use.

Also, remember that the crisis response resources are phone or text-based. For neighbors facing crises related to mental health or domestic violence, these hotlines can be an important help and do not require a computer.

Accessing the public benefits that are available in your state can be confusing for folks. But with these guides to get started, the process can be much easier and less time-consuming.

Note: Most of the public benefits expanded under the CARES Act are not available to undocumented immigrants. The ELCA’s AMMPARO ministry has shared a spreadsheet of resources on its Facebook page to help non-citizen neighbors find the support they need.