At the 2016 ELCA Churchwide Assembly, ELCA World Hunger staff fielded questions and gathered feedback from the folks packing a room in the New Orleans’ Ernest Morial Convention Center. For an hour, we shared updates, heard comments about our resources and programs, and listened to stories of congregations responding to hunger and poverty in communities across the ELCA. At the very end of our time, amidst the ruffling of papers and gathering of bags as people prepared to leave for the next session, an energetic man approached the microphone. In a few short words, he silenced the room with his story.

“I have sat here and listened as everyone has talked,” he began, a thin smile on his face. “Now, I decided, I want to talk.” We sat riveted as he described how the violence of civil war came to his hometown in Sudan and how it claimed the lives of so many of his friends and neighbors. He told us how he chased after his brother, both of them running alongside other young boys, toward a truck that promised safety and an escape from the conflict. The truck bore the letters “LWF,” an acronym he didn’t know at the time stood for Lutheran World Federation. His older brother pushed him on the truck, and he began a years-long journey, first to a refugee camp and then to Michigan, where he settled and started a family.

“L. W. F. Before I even knew what those letters meant,” he said, “they saved my life.”

Today marks the 17th annual World Refugee Day, a day set aside by the United Nations to draw attention to the challenges faced by people around the world who have fled their homes – by choice or compulsion – seeking safety, opportunity, and a place to call home. It is a chance to celebrate the individuals and families who have built new lives in new places, to mourn those who have lost their lives while on the move, and, for Lutherans, to remember our own history as migrants and refugees.

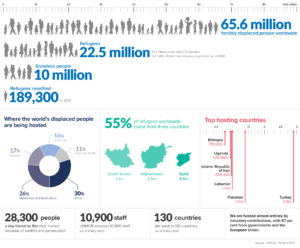

The United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that more than 65 million people are displaced from their homes around the world, with more than 22 million fleeing violence, poverty, and persecution as refugees. This is an almost-unprecedented number of people on the move, and the work of nonprofit organizations, churches and community partners accompanying refugees and migrants has rarely been so important.

Through ELCA World Hunger and Lutheran Disaster Response, our church accompanies our neighbors in their home communities, in transit and temporary shelters, in refugee camps, and in their new homes. The intersection between conflict, migration and food insecurity is complex but undeniable. In a study released earlier this year, the World Food Programme (WFP) found that for every percentage increase in food insecurity, refugee outflows from a country increase by 1.9 percent, demonstrating the significant role food insecurity plays in forcing people from their homes. Moreover, the WFP found that food insecurity also plays a role in increasing the intensity and duration of armed conflict, another significant factor that pushes people to seek safety in other regions and countries.

Working through companions and partners, ELCA World Hunger supports projects aimed at sustainably bolstering food security, making it possible for people to feed themselves and their families in their own hometowns. For those who cannot stay in their homes, the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) administers refugee camps like Kakuma and Dadaab in Kenya. Kakuma, located in northwestern Kenya, was established by the UN in 1992 with a capacity for 125,000 refugees, most of whom were fleeing Sudan. Today, more than 160,000 refugees live in the camp. While it was never intended to be a permanent home, many refugees spend upwards of ten years living in Kakuma, waiting to return to their homes or to resettle in a new place.

Adapting to life in Kakuma is not easy, but many residents, with the support of LWF programs, find ways to use their talents and skills while in the camp. Programs that focus on education and improved livelihoods, supported in part by ELCA World Hunger, address some of the critical barriers residents face. One key opportunity for economic empowerment for residents is through village savings and loan programs (VSLAs). In a VSLA, community members pool their savings and provide small loans to individuals to start or grow a business. Once the business turns a profit, the money is repaid and loaned out to another VSLA member. This gives folks in Kakuma the resources they need to support themselves and their families. Moreover, much of the work administered by LWF, including efforts toward education, economic empowerment, and human rights, is done with the participation of both refugees in the camp and members of the local host community, many of whom face their own challenges related to poverty and hunger.

KTN News in Kenya recently featured a story of a thriving bakery that started through a loan from a VSLA:

Programs like this are important ways our church accompanies our neighbors as they build lives for themselves far from home. As the number of displaced people around the world increases, accompaniment of internally displaced persons, refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers continues to meet a critical need.

At the churchwide assembly, we were reminded of that need and the role that the ELCA and our companions can play in a world facing a refugee crisis. But we were also reminded of how much our communities stand to gain from the gifts refugees and migrants have to offer. The former “lost boy of Sudan” who didn’t know what “LWF” meant when he first saw the letters is now in the TEEM program of the ELCA, developing his skills of leadership to offer his talents within the church he now calls his own.