As new as the COVID-19 pandemic is to us living today, it is far from the first pandemic the church has had to address. One of the deadliest was the bubonic plague, which ravaged Europe in the mid-1300s, killing millions (estimates range from 25 to 50 million people.) In 1527, the plague re-emerged. When it hit Wittenberg in late summer, the University of Wittenberg closed. The students were sent home, and many residents self-quarantined to avoid the deadly sickness.

Martin Luther, recovering from his own illness, responded to an earnest plea from Johann Hess, the pastor at Breslau. Hess’ central question was thus: as everyone else sequestered themselves in isolation, “is it proper for a Christian to run away from a deadly plague”? Luther responded with his letter “Whether One May Flee from a Deadly Plague.” Below are four lessons we can learn from Luther’s response, both for our situation today and for our long-term approach to health and wellness.

Good health matters to God.

The Lutheran World Federation’s “Waking the Giant” initiative invites member churches to reflect on the many ways churches are already contributing to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal of good health and well-being for all – and to consider new ways churches can be part of this work. Accompanying communities as they seek good health for all people is a cornerstone of ELCA World Hunger. As a member of the LWF, and with the United States being a target country of “Waking the Giant,” the ELCA continues to accompany companions and partners in this initiative and to work toward the goal of good health here in the US and the Caribbean.

This focus on health is nothing new for the church. Some of the earliest hospitals were founded by Christian leaders, and history is full of examples of churches accompanying people living with illness, from the Plague of Justinian in the 600s to today.

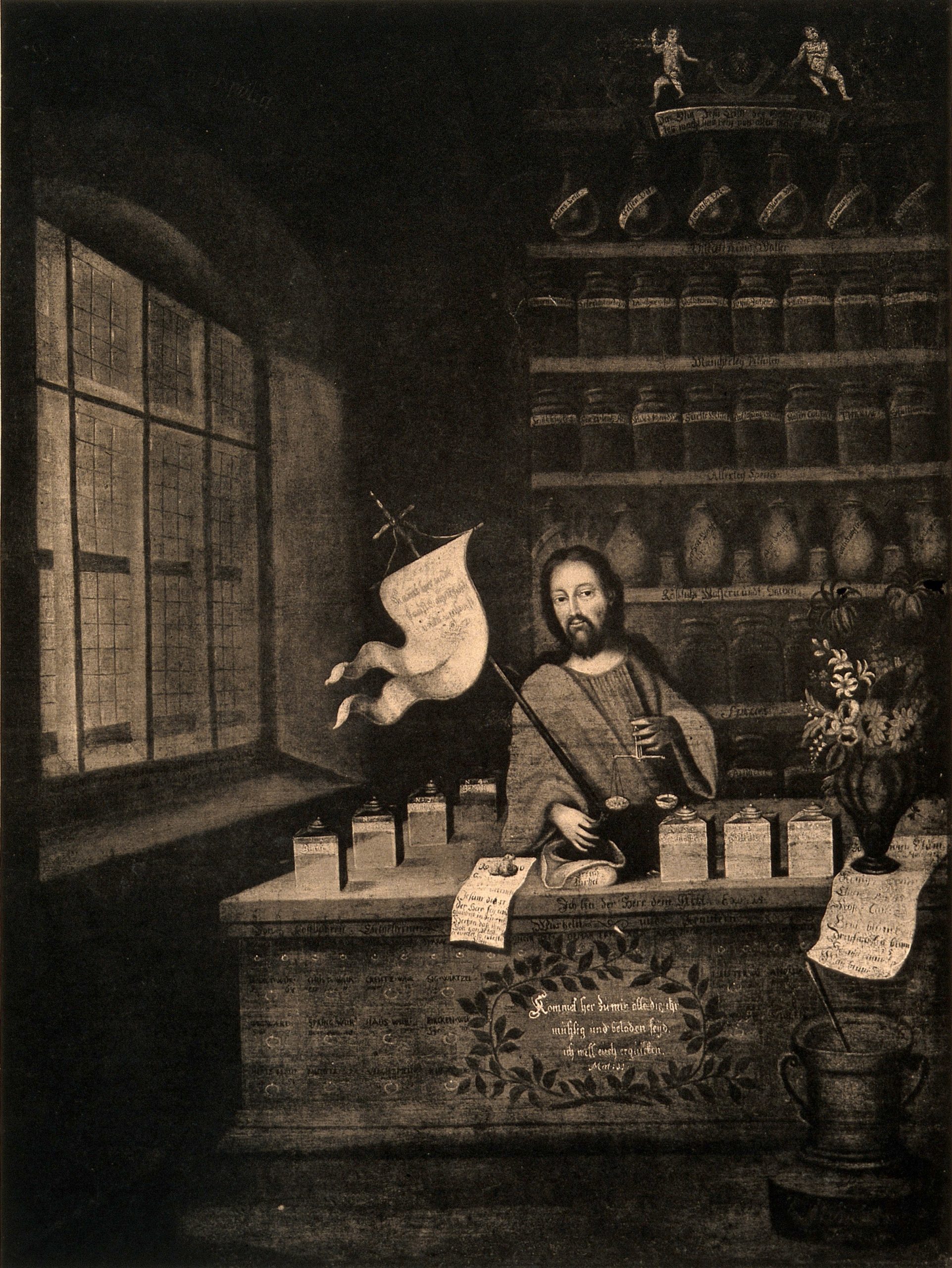

For Luther, this work was grounded in two claims of faith. First, the church is called to service of the neighbor, particularly in times of distress. Citing Matthew 25:41-46, Luther argued in his response to Hess that “we are bound to each other in such a way that no one may forsake the other in his distress but is obliged to assist and help him as he himself would like to be helped.” To help one’s neighbor in times of illness is to serve Christ. Second, Luther believed that medicines, treatments and intelligence are God’s gifts so that “we can live in good health.” Recalling St. Augustine’s image of Christ as the “physician,” Luther counsels Hess that God cares both for the spiritual needs of the soul as well as the physical needs of body. Simply put, good health matters to God.

Christ as apothecary; suggesting the idea of Christ as the universal healer. Reproduction of a photograph of an oil painting after J. Marie Appeli, 1731. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

And good health matters to God’s people.

So, can one flee a plague if one’s life might be threatened? Luther’s answer is not simple, in part because the question itself is a bit of a problem. When we ask, “what ought we to do in a crisis?” it’s often asked from the perspective of obedience. “Can one flee a deadly plague?” is really a way of asking, “Can I flee a deadly plague and still be doing what God wants me to do?”

Of course, for Luther, the life of faith isn’t about obediently completing certain tasks. It’s about responding in love to the neighbor. So, whether one can flee a crisis to save oneself depends: what is in the best interest of the neighbor? Luther offers a well-reasoned defense of self-preservation in the face of pandemic. BUT, he is quick to temper this by saying that self-preservation is only permissible if we are certain our neighbors are taken care of. It’s one thing to leave a neighbor with a network of other supporters. It’s a very different thing to leave a neighbor alone, without aid.

What ought we to do in a crisis? For Lutherans, the answer isn’t obedience to a universal rule but rather a question of discernment – what is in the best interest of our neighbor? Accompanying the neighbor is the end against which our methods should be measured. This includes helping care for the bodily needs, as well as the spiritual, as we’ll see below.

That said, Luther also wanted his readers to consider whether their presence was more harmful than helpful. What, besides self-preservation, ought to shape our response to a pandemic? And, what might love of neighbor look like?

Pray…then work.

Therefore I shall ask God mercifully to protect us. Then I shall fumigate, help purify the air, administer medicine, and take it. I shall avoid places and persons where my presence is not needed in order not to become contaminated and thus perchance infect and pollute others.

Leaving aside his questionable belief that epidemics are spread by “pestinential breath,” Luther’s description sounds timely, still today. What he is describing, essentially, is social distancing. Pray, yes, but take practical steps to avoid infecting yourself and others, he claims.

Of course, Luther is not discouraging prayer. But in his day, as in ours, there are those who believe that prayer, faith or other spiritual powers can protect them, and so they do not need to take other precautions. Luther called this sinning “on the right hand.” Those who rely solely on faith as a sort of spiritual, magical power without taking advantage of the other gifts of God, such as intelligence and medicine, “are much too rash and reckless, tempting God and disregarding everything which might counteract death and the plague.” Contrary to this, Luther argued that Christians are called to take necessary, practical steps to protect physical health.

He went further, too, arguing that governments should “maintain municipal homes and hospitals staffed with people to take care of the sick so that patients from private homes can be sent there.” This, he wrote, would be “a fine, commendable, and Christian arrangement to which everyone should offer generous help and contributions, particularly the government.” This echoes what Luther says elsewhere, namely that government, too, is a gift of God for our well-being. As such, those in power are obligated by their station to help. Churches, for their part, are called to assist in this work – and to hold government accountable when it fails.

Listen to the experts.

In his letter, Luther admonishes readers of the importance of taking medicine, of self-quarantining, of hygiene and other practical measures. He also offers his proposals for care for the soul, responding as we would expect a pastor to do. But throughout, what is very interesting is Luther’s deference to medical experts. Sure, he is more than qualified to offer spiritual care advice, and he does so. But when it comes to specifics about avoiding illness, he is more hesitant.

This is clearest near the end of the letter, where he writes about burials. Because of the spread of the bubonic plague, there was debate about how to handle the dead bodies of victims. Luther writes,

I leave it to the doctors of medicine and others with greater experience than mine in such matters to decide whether it is dangerous to maintain cemeteries within the city limits. I do not know and do not claim to understand whether vapors and mists arise out of graves to pollute the air.

What to do with dead bodies is no small matter in any religion. Christians, like other faiths, have specific rituals and practices, informed by our beliefs about death and life. It’s not too much to assume that deferring to medical authorities here is a pretty significant step for Luther. It means giving up the church’s right over its dead. Luther does a bit of fancy prooftexting of scripture to support not burying corpses within the city limits in his letter. But in the end, his thought process is clear: when it comes to health, defer to those who have been gifted by God with expertise. And recognize their work as one of the ways God is active in our world, promoting good health for all.

Luther’s understanding of health and illness may be scientifically outdated, but his nuanced approach to the church’s vocation during times of crisis can give us food for thought. Health and wellness for all are not ideals for the future reign of God but practical realities the church is called to pursue today. Accompanying neighbors facing illness and working to keep communities healthy is an important way to reduce hunger and to discover God at work in our midst, through community leaders, medical experts, first responders and one another. And we see this in the hospitals, maternal and child care programs, health education initiatives and other ministries ELCA World Hunger supports.

Health was part of God’s intention for the world long before it was a Sustainable Development Goal. Working together toward this – even if that means, right now, working and living apart for many of us – is where the church is called to be, and where it has been during the “plagues” of the past.

All quotes cited above are from Martin Luther, “Whether One May Flee from a Deadly Plague (1527),” in Timothy F. Lull and William R. Russell, eds. Martin Luther’s Basic Theological Writings, 3rd edition (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2012), 475-487.