Synod assembly season is in full-swing in the ELCA, and many readers of this blog will be helping raise awareness about hunger and poverty among their fellow Lutherans in the coming weeks. Outside of assemblies and events, we often are asked for statistics and facts about hunger and poverty for congregations and groups. So, ELCA World Hunger’s education team has put together a presentation with stats on global and domestic hunger and poverty that you can share.

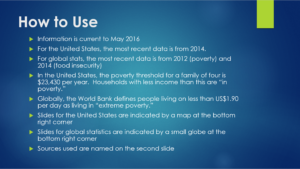

The stats in the slides are from the most up-to-date sources we have. This will differ for each of the four areas: US hunger, US poverty, global hunger, and global poverty. Each of the sources we used are listed in the second slide, so you can read more about the measurements. Follow the link at the end to download the whole presentation.

Thank you for all you do to help your community learn more about hunger and poverty and how together we can work for a just world in which all are fed!

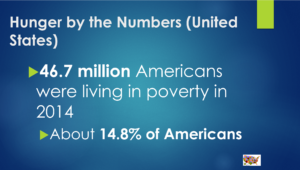

How many people in the US were living in poverty in 2014?

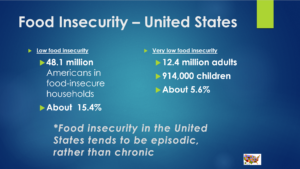

Food insecurity means lacking access to sufficient amounts of affordable, healthy foods to live an active life. In the US, food insecurity tends to be “episodic,” which means that there may be times when people can’t access the food they need. This may be because of seasonal work or insufficient benefits that run out before the end of the month.

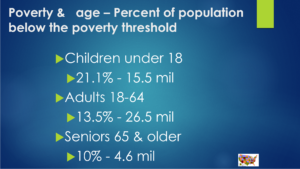

What percentage of people in different age groups experience poverty in the United States?

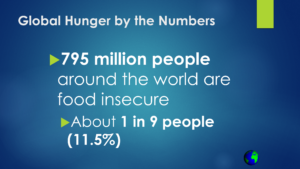

Global hunger tends to be chronic, rather than episodic, which means that hunger is often a daily reality, leading to problems like malnutrition and stunting. The good news is, the number has fallen in the last 30 years. The bad news is, it is still too high.

How prevalent is undernourishment in different regions of the world?

The World Bank has begun using a new standard for global extreme poverty – $1.90 per day. This line better reflects real costs of food, clothing, and shelter around the world. Again, the number is falling, with the World Bank projecting that about 700 million people will be living in extreme poverty in 2015. Hopeful, but there is more work to be done.

To download the presentation, click here.