At midnight last night, my brother, father, and I set off sparklers by the light of the blue moon. Like a few million other people in our time zone, we counted down the minutes and then the seconds until the new year began.

At midnight last night, my brother, father, and I set off sparklers by the light of the blue moon. Like a few million other people in our time zone, we counted down the minutes and then the seconds until the new year began.

New Year’s Eve used to be the only time of year we really thought in seconds. But as everything in our life speeds up—as work days extend to 24/7, as we tap our fingers impatiently for the few seconds it takes to download an email or a web page, as deadlines shorten to yesterday and demands on our present escalate—the seconds and minutes of our present moment are overwhelming our ability to think about the future. Just when we need to get to work creating one that doesn’t kill ourselves or our planet!

Many times when Christians talk about the future, they think about life after death. About 25 years ago, I was standing behind an ironing board in front of a Walgreen’s in Chicago, gathering signatures for an anti-nuclear petition. After listening to my heartfelt pitch, a young woman responded, “As Christians, shouldn’t we be hoping the world will end, so that the reign of Christ can begin?” In 1984, this left me speechless; now I would quote Bonhoeffer: “It may be that the day of judgment will dawn tomorrow; in that case, we shall gladly stop working for a better future. But not before.”

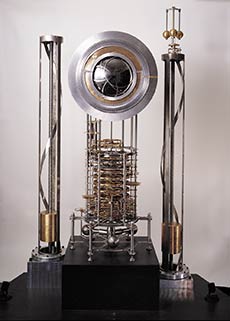

One way to enrich our ability to engage the future might be to begin the new year by contemplating the long, long, LONG view of the future espoused by the Long Now Foundation, formed to “provide counterpoint to today’s ‘faster/cheaper’ mind set and promote ‘slower/better’ thinking.” Its proposed 10,000 Year Clock “ticks once a year, bongs once a century, and the cuckoo comes out every millennium.” “The point is to explore whatever may be helpful for thinking, understanding, and acting responsibly over long periods of time,” says cofounder Stewart Brand. (Remember the Whole Earth Catalog?)

A prototype of the 10,000 Year Clock in San Francisco (see the photo above) introduced me to the possibilities of seeing time as slow and spacious rather than fast and crowded. It seemed to fit nicely with Amitai Etzioni’s call for a cultural megalogue “about the relationship between consumerism and human flourishing,” which I got all excited about in this post. Changing our imagination of the future might change the way we value it, which in turn might change the way we live in our present, and help our society shift away from consumerism.

For how we see time has a lot to do with how we consume. In the New York Times, Damon Darlin recently noted that frugality—poor, maligned, unfashionable frugality—is actually the practice of an optimist. “If you expect good things in the future, you’re inclined to save money for that event. If you are a pessimist, you might as well spend everything now.” Change the word money to environment, and these sentences still ring true.

Can you imagine how our day-to-day choices might impact the children of our children’s children’s children? My son is only 22. Being a grandmother is something I can hardly imagine. But if I start taking those distant progeny for granted, I might live differently.

Ten thousand years—are you ready?

Anne Basye, “Sustaining Simplicity”