The word advocacy does not appear in the letter to Philemon. Interestingly, the word commonly translated as advocate (paraclete) appears a few times in John’s gospel, once in 1 John and nowhere else in the New Testament. But Paul’s letter to Philemon is a helpful example of how theology and practicality come together in a personal advocacy-like appeal. It seems lazy to consider only a few verses of Philemon since the book is so short, but the following passage provides a glimpse at Paul’s tone and strategy.

For this reason, though I am bold enough in Christ to command you to do your duty, yet I would rather appeal to you on the basis of love—and I, Paul, do this as an old man, and now also as a prisoner of Christ Jesus. I am appealing to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I have become during my imprisonment. Formerly he was useless to you, but now he is indeed useful both to you and to me. I am sending him, that is, my own heart, back to you. I wanted to keep him with me, so that he might be of service to me in your place during my imprisonment for the gospel; but I preferred to do nothing without your consent, in order that your good deed might be voluntary and not something forced. (Philemon 1:8-14)

Onesimus was a slave in Philemon’s house who, for some reason, may have wronged Philemon and somehow found Paul. We can only guess if Onesimus knew of Paul’s influence or had hoped for a result other than the one Paul was willing to provide. But from this letter it is evident that Paul has chosen to come alongside Onesimus and speak out on his behalf to someone who has sway over Onesimus’ future. One of the key moves in this letter is Paul’s emphasis on the change in Onesimus’ status. The change from “useless” to “useful” may be more rhetorical than descriptive, but the change from slave to beloved brother (v.16) demands more attention.

Paul is able to call Philemon brother because of the new identity they share in Christ. His appeal is for Philemon to see his relationship with Onesimus in the same way, that is, through Christ. This of course hadn’t settled the issue of slavery or how Christians should respond to it as an institution. But his appeal works in a different way. Paul appeals to Philemon’s faith in Christ knowing that it is something that has shaped him as well as the community to which he belongs. Since this faith has influenced Philemon’s attitude, Paul is hopeful that it will influence his relationships as well. In this case, Philemon has a claim on Onesimus that Paul wants to contextualize in terms of faith in Christ. Since Christ’s self-giving love demonstrates what laying down power looks like, Paul is presenting Philemon with the opportunity to do the same with Onesimus. He is not appealing to some general ethic of looking out for the interest of someone in need (which is not a uniquely Christian idea), but Paul is asking Philemon to set aside worldly power for the sake of Christian love. At some unidentified point, the two become incompatible.

When interpreting Philemon it is difficult to ignore the passages that seem slightly passive aggressive, if not opaque. First is the fact that the letter is addressed not just to Philemon, but to the church in his home. What was Paul hoping the others would do with this? He also notes that he is bold enough to command Philemon but chooses not to. What function does this serve if not to appeal to Paul’s stature in the community? There is another subtle move. Paul has been building his case through verse 13, then backs off just for a moment to recognize Philemon’s agency in the matter by stating that he wants this to be something voluntary rather than forced. Paul is not afraid to tell Philemon what he should do but he concedes that the choice is Philemon’s. Finally, Paul tells Philemon to get the guest room ready because he is planning to visit. The request may of course be innocent, but it may also be Paul’s way of saying he is coming to see for himself how things shook out.

What does this mean for how we understand advocacy? There may be some useful tactics for us to employ. However, it probably isn’t as simple as trying to identify parallels between this letter and our contemporary context; a significant discrepancy being that we aren’t usually on equal footing with Paul regarding the leveraging ability of our advocacy efforts. It requires a special relationship to even be received like Paul. I would offer that it has something substantial to say to us about how we understand power. Whether we have the influence of Paul or not, aligning our voice (individual and collective) with another’s need, especially the most vulnerable, is part of how we express our faith in Christ. In this way it is both with humility and boldness that we write to legislators, seek to change policy, and try to build relationships with our neighbors.

To find out more about advocacy efforts and resources in the ELCA visit http://www.elca.org/Our-Work/Publicly-Engaged-Church/Advocacy.

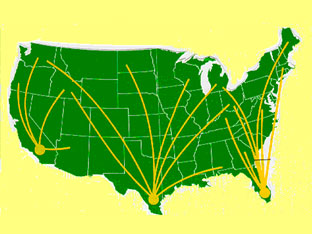

In Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies, Holmes attempts to better understand the “social and symbolic context of suffering among migrant laborers” (29). The book begins with a personal account of a dangerous border crossing, then records his work alongside a particular group of Triqui people (an indigenous group in what is now the Mexican state of Oaxaca) through harvest fields in Washington, California and back to Oaxaca. His explorations progress with the hope that his observations will help change public opinion, practices and policies (29).

In Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies, Holmes attempts to better understand the “social and symbolic context of suffering among migrant laborers” (29). The book begins with a personal account of a dangerous border crossing, then records his work alongside a particular group of Triqui people (an indigenous group in what is now the Mexican state of Oaxaca) through harvest fields in Washington, California and back to Oaxaca. His explorations progress with the hope that his observations will help change public opinion, practices and policies (29).  Map showing major migration streams in the United States.

Map showing major migration streams in the United States. Pebbles’ daughter receives SNAP benefits each month, but Pebbles herself does not because she receives a small amount of Social Security which “barely pays rent.” Getting benefits for her daughter is a burdensome process that requires “a lot of patience.” Still, she says, “I have to do it.” Without help from other family members, her daughter depends on SNAP to eat, though even with the meager benefit she receives, both Pebbles and her daughter were going hungry by the last week of each month. SNAP helped a lot, but it didn’t keep them from going hungry.

Pebbles’ daughter receives SNAP benefits each month, but Pebbles herself does not because she receives a small amount of Social Security which “barely pays rent.” Getting benefits for her daughter is a burdensome process that requires “a lot of patience.” Still, she says, “I have to do it.” Without help from other family members, her daughter depends on SNAP to eat, though even with the meager benefit she receives, both Pebbles and her daughter were going hungry by the last week of each month. SNAP helped a lot, but it didn’t keep them from going hungry. captures this divide in writing that is perceptive and prophetic, even if not always persuasive. Lupton tells of the church in Mexico that was painted six times by six groups one summer, the gift-giving program that left the fathers of children feeling emasculated and inadequate, and the tile floor in a Cuban seminary that was inexpertly laid by novice volunteers as skilled local laborers were left without work.

captures this divide in writing that is perceptive and prophetic, even if not always persuasive. Lupton tells of the church in Mexico that was painted six times by six groups one summer, the gift-giving program that left the fathers of children feeling emasculated and inadequate, and the tile floor in a Cuban seminary that was inexpertly laid by novice volunteers as skilled local laborers were left without work.