After a lifetime of Sundays, worship can seem so rote, so mechanical. Sermon lessons blend together, and we can float through liturgy on autopilot. But as I was reminded this weekend, once in a while something as simple as a children’s sermon can catch us off-guard, grab us, and force us to pay closer attention.

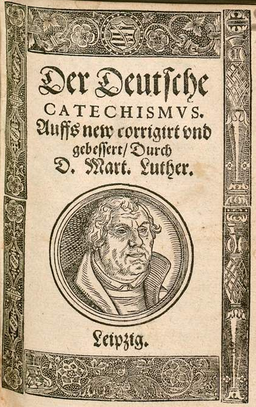

This Transfiguration Sunday, in preparation for Lent, the congregation I was with watched as the pastor gathered the children in front of the altar. Posted on the railings were hand-written signs proclaiming “Alleluia.” The pastor clutched her guitar while talking with the children about the meaning of the word and asked them about when they had heard it before in worship. Then she explained what would happen this week, when “Alleluia” is excised from our sacred speech as we journey through Lent.

She presented them with a box and invited them to remove the signs and place them therein. Then, she rose and began strumming an “Alleluia” verse as the children placed the colorful signs in the monochrome chest, burying the “Alleluia” until Easter.

This wasn’t new or novel. Lutheran churches around the world will do the same this week. The children’s sermon and that final ritual was seasonally appropriate, liturgically relevant. Catechetically sound. And it was also one of the saddest sights I have seen on a Sunday morning. Each child carefully laid a handmade sign in the box, and on that Transfiguration Day, the signs became lifeless, the box like a tomb. In that moment, the death toward which we will accompany Jesus this season became real, and with it the many deaths that have come after Jesus’ own.

The simple act of youth during that children’s sermon was a powerful ritual, made all the more poignant by the lilting tune the pastor strummed and sang. It was as if the juxtaposition of the happy tune and the grave act encapsulated all the tension and paradox within Lutheran faith. It was profoundly solemn and somber, even as the pastor held out hope for the opening of the box on Easter. It was a sermon for the disciples in the shadow of the cross, who lose their innocence as their Messiah is tried and convicted. It was a sermon about the deep sorrow of Lent, and the deeper sorrow of God for a fallen world. It was a children’s sermon for people who can no longer be children.

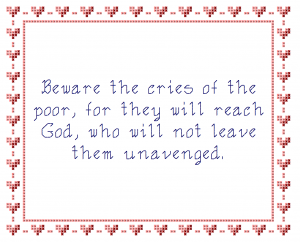

It recalled to me the millions of children who must keep their own “Alleluias” buried all year round:

- In 2016 (the last year for which we have data), children in nearly 300,000 households across the United States didn’t know where their next meal would come from.

- On a single night in January 2017, the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s point-in-time count found nearly 110,000 children living with families that were homeless. Another 4,800 children under age 18 were unaccompanied by any adult and homeless.

- The World Health Organization estimates that malnutrition was a factor in 45 percent of the 5.6 million deaths of children under the age of five in 2016.

- UNICEF estimates that 50 million children around the world are “on the move” – fleeing violence, disaster, and poverty as refugees or migrants.

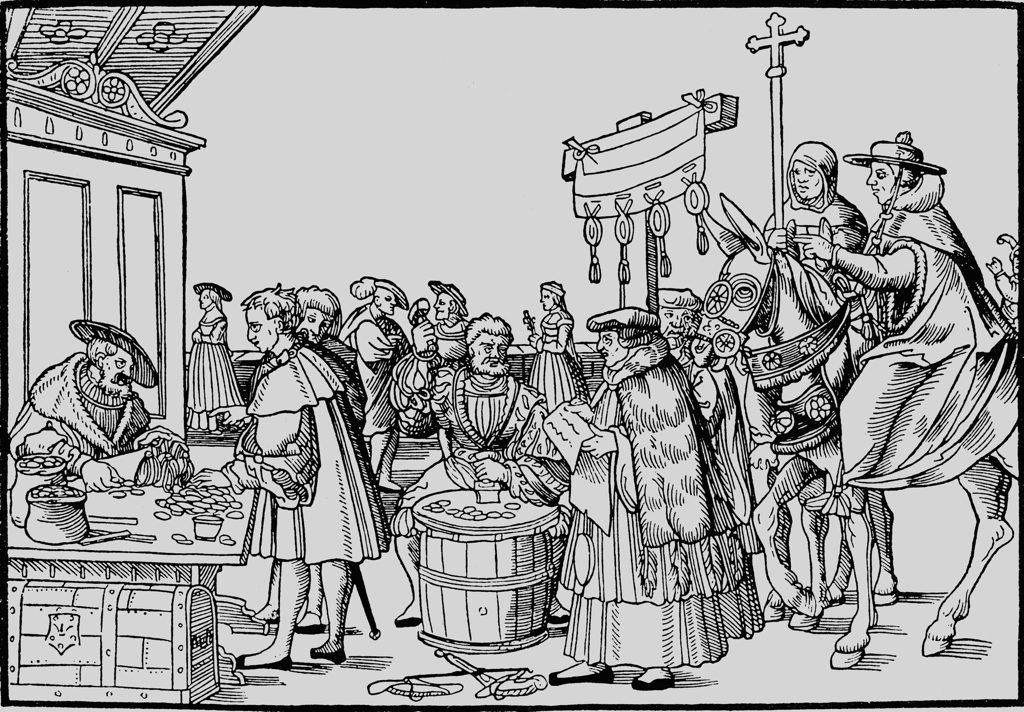

As we bury the “Alleluia” in our congregations this week, as we journey through Lent with its sacrifice, repentance, and critical self-examination, our world longs for the “Alleluia” that will not remain buried. Seeing this ritual play out so vividly at the foot of the altar this Sunday, I was reminded why we do this – why we accompany our neighbors in need, why we strive for a world where all are fed, and why we refuse to believe that this is an impossible goal. We do this because we know we must know we cling in faith to that promise that the “Alleluia” must not, cannot, and shall not stay buried forever. That in life, there is death, and in death there is life. We do this because we know that, outside the rhythm of our liturgical season, the “Alleluia” has been released forever by the resurrection of Christ, so that no shout of joy ought to be stifled by hunger, silenced by injustice, or hidden by pain. We know that God’s intention is for our “Alleluia” to resound – forcefully, loudly, boldly – now, in this world, in this time.

As we reflect on the buried “Alleluia” this Lent, we also remember that grace continues to abound in our world through God’s continued work through our church and our neighbors:

- Through the Lutheran Church in Rwanda’s “Integrated Child Support and Welfare” project, more than 130 vulnerable children received the financial support they needed to continue their education in 2017;

- Last year, 25 beehives provided by the Lutheran Conference and Mission Home produced over 660 pounds of honey, which Roma families in Hungary used to earn stable income and provide for their children;

- In 2016, Boise Rescue Mission Ministries in Idaho served nearly 350,000 meals to people in need and helped 600 individuals transition from homelessness to independent living. This life-changing work will continue in 2018.

All of these ministries – and nearly 600 more – were supported last year by gifts to ELCA World Hunger. And all of them bear prophetic witness against the injustice and exclusion that can bury cries of joy beneath mounting need.

Even as we reflect on sin, death and our dependence on God in Lent – even as we ritually bury the “Alleluia” in our sanctuaries, we know that God’s work in the world continues. The work of ending hunger goes on with faith in a promised future where all will be fed. We share in God’s work with hope, joy and faith. And we do this work because we know by faith that when it comes to the seemingly insurmountable problems of hunger, poverty, and human need, God will have the final word. And that word will be “Alleluia!”

Ryan P. Cumming, Ph.D., is the program director of hunger education with ELCA World Hunger. He can be reached at Ryan.Cumming@ELCA.org.