Peter Singer, The Life You Can Save: How to Do Your Part to End World Poverty. New York: Random House, 2010.

I imagine it takes a good amount of restraint (and/or editorial skill) for a philosopher to present an argument, offer supporting anecdotes, and still manage to deliver an accessible read that comes in under 200 pages. In this account Singer makes the case for charitable giving, specifically charity that is directed toward the most vulnerable people. The argument, as Singer outlines, provides enough of a hook that readers could find themselves intrigued by his case even if they disagree with his underlying assumptions. It can be summed up in this way: “in order to be good people, we must give until if we gave more, we would be sacrificing something nearly as important as the bad things our donation can prevent” (140).

Singer shapes the claim and its premises on a utilitarian philosophy that appears demanding and unsustainable, but coalesces into a realistic approach by the end of the book. Before he gets there, Singer identifies and counters some common objections to giving. In a section entitled “Human Nature,” he tackles some psychological factors for why we don’t give more. Singer uses moral dilemmas to explore these, then highlights examples of philanthropic efforts to explain how cultures of giving are created. Having made the case for giving, Singer turns his attention to the state of aid, providing examples of the work of certain aid organizations. Even here, Singer doesn’t shy away from some of the challenges and difficulties aid organizations face. Of these challenges, he states, “the uncertainty about the impact of aid does not eliminate our obligation to give” (124). His main argument in this section is that significant life-improving work can be done at a relatively minor cost.

In the final section of the book Singer presents “A New Standard for Giving.” Perhaps recognizing one of the deep-seated rationalizations for not giving, he turns his attention to parents’ concern for their own children. He presents a challenge by stating that when we consider moral imperatives we don’t always assume that parents ought to put their children first. This works on a philosophical level, but Singer then points out that if an obligation is going to be accepted widely, we have to recognize that parents will meet the basic needs of their own children before that of strangers. Singer, by looking at how we defend moral obligations, though, argues that luxuries spent on one’s children are not justifiable ahead of the basic needs of others.

Singer avoids sounding prescriptive throughout the book until it comes to laying out his realistic approach to charitable giving. He suggests that people give 5% of their annual income, recognizing that some could comfortably give this amount and more, while others would find it difficult. He goes on to apply a progressive suggested donation based on the income tax bracket, which would, he calculates, raise eight times the amount of money required to meet the Millennium Development Goals. Singer’s recommendation is mainly for those making over $100,000 per year. For those who find themselves under this amount his message is essentially to think about the extra spending money we have and to cut back on luxuries. He demurs at defining this, but the logical conclusion of his philosophy is that a luxury would be anything more than what would be considered a basic need.

Those who are looking to make a case for charitable giving may appreciate the directness and consistency of the argument in this book. It may also appeal to those who appreciate debate, since Singer relies on his premises to pursue his main argument. But it is in the terms of the argument where we see the greatest contrast between Singer’s philosophy and a faith-based one. Singer acknowledges that there is evidence for charitable giving within the teachings of the major world religions, but his argument is not made on religious terms. As a result, his case progresses on a universalist approach, which runs the risk of undermining the efficacy of faith traditions and their competing, contextualized ethics.

Singer’s argument begins, “in order to be good people…” His argument is built on the assumption that charitable giving, specifically to the poorest and most vulnerable, makes us better people. Lutherans would reverse course, arguing that we are justified in Christ, which leads us to be giving. Even though we would start from an entirely different foundation or central claim than Singer, this does not mean his argument is irrelevant. Singer’s presentation essentially points out the reality of sin and injustice: some are very wealthy, many people are suffering, many more can do at least something about it. After reframing his argument, our efforts are better spent answering his challenge from within our own tradition. This book can be helpful in a study of what it means to “be good,” or as a discussion starter for groups looking to study stewardship. From a Christian perspective, one book that raises similar questions is Ron Sider’s Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger. Like Singer, he points out the disparities between the affluent and impoverished but builds the case for charitable giving from within the Christian tradition. Another book that Lutherans would appreciate for the theological connections is Samuel Torvend’s Luther and the Hungry Poor.

Henry Martinez is an education associate for ELCA World Hunger.

In Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies, Holmes attempts to better understand the “social and symbolic context of suffering among migrant laborers” (29). The book begins with a personal account of a dangerous border crossing, then records his work alongside a particular group of Triqui people (an indigenous group in what is now the Mexican state of Oaxaca) through harvest fields in Washington, California and back to Oaxaca. His explorations progress with the hope that his observations will help change public opinion, practices and policies (29).

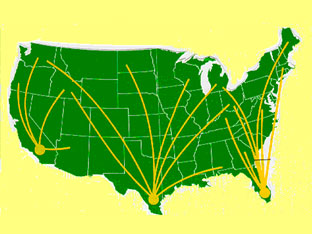

In Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies, Holmes attempts to better understand the “social and symbolic context of suffering among migrant laborers” (29). The book begins with a personal account of a dangerous border crossing, then records his work alongside a particular group of Triqui people (an indigenous group in what is now the Mexican state of Oaxaca) through harvest fields in Washington, California and back to Oaxaca. His explorations progress with the hope that his observations will help change public opinion, practices and policies (29).  Map showing major migration streams in the United States.

Map showing major migration streams in the United States.