In observance of Arab American Heritage Month, ELCA Racial Justice Ministries invited Rev. Dr. Niveen Ibrahim Sarras to share her thoughts on this topic with our readers.

People in the West often assume that Arab Christians were converted from Islam to Christianity by Western missionaries. However, Arab Christians have always existed in the Middle East and have enjoyed significant influence in the Arabian Peninsula.

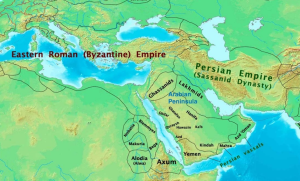

To understand Arab Christians, it helps to know the geography of the peninsula. Arabia, known as Jazīrat Al-ʿArab (“Island of the Arabs”) in Arabic, extends beyond present-day Saudi Arabia, encompassing the Arabian Peninsula (bordered by the Red Sea to the west), the Gulf of Aden to the south, the Arabian Sea to the southeast, and the Gulf of Oman and Persian Gulf (also known as the Arabian Gulf) to the east.

Arabia was inhabited by nomadic bedouins who survived through hunting, mercenary work, trade and raids on other tribes. As noted in Acts 2:11, Arab merchants traveled to Palestine for business. Christian tribes such as the Ghassanids, Lakhmids, Banu Taghlib, Banu Tamim and Nabataeans were spread across the peninsula, originating from Yemen and migrating to the Levant after the destruction of the Marib Dam in the sixth century BCE. By the fifth century CE most of these tribes had converted to Christianity. Arab Christians in the peninsula spoke and prayed in Arabic, yet their liturgical and confessional writings were in Syriac.[1]

In 732 CE, Arab forces influenced by Islam conquered the Levant, a Greco-Roman region that had previously been part of the Byzantine Empire. Muslims spread their Arabic language with each conquest. The Levant was predominantly inhabited by non-Arab Christians, possibly descendants of various ancient civilizations. Christian communities in the conquered territories spoke Greek, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian and Ethiopian languages.[2] Communities in Damascus and Baghdad were predominantly Arameans, using Aramaic for theology and liturgy, whereas those in Palestine, Jordan and Sinai utilized Greek ecclesiastically but Aramaic/Syriac locally. Over time Christians in the Levant and Egypt became Arabized through the imposition of the Arabic language. The Melkite Church was the first to adopt Arabic for worship.[3]

In the eighth century CE, Arabized Christian families in the Levant were drawn to Muslim power, leading them to convert to Islam. Christians held high positions and contributed to intellectual life under Muslim rule but faced pressure to convert. Muslim authorities imposed a poll tax on Arab Christians who refused to convert,[4] so they translated their religious texts into Arabic and developed apologetics to defend their faith. After the Crusades, Muslims imposed harsh policies on Christians, prompting resentment. Arabization accelerated through translation efforts and Islamic influences.

The Ottoman Empire’s occupation of the Middle East, which lasted from 1516 to 1917. led to “Turkification” efforts, and this cultural oppression provoked an Arab nationalist movement. Arab Christians revived the Arabic language and culture, but tribalism frustrated their efforts to form a unified Arab identity. Despite these differing identities, Islam’s influence remains strong among Arab Christians.

In sum, Christians in the conquered territories became Arabized when the Arabic language was imposed upon them. In other words, they are not Arabs by ethnic or race bound but by the Arabic language.

The Rev. Niveen Ibrahim Sarras was born and raised in Bethlehem, Palestine. She is the first Palestinian woman ordained to the ministry of Word and Sacrament in the ELCA. Her passion for the Bible started through attending Sunday school at the Lutheran Church of the Reformation and attending Lutheran school in Bethlehem.

The Rev. Niveen Ibrahim Sarras was born and raised in Bethlehem, Palestine. She is the first Palestinian woman ordained to the ministry of Word and Sacrament in the ELCA. Her passion for the Bible started through attending Sunday school at the Lutheran Church of the Reformation and attending Lutheran school in Bethlehem.

Hungry for a deeper knowledge of Scripture and eager to answer God’s call to ministry, Rev. Sarras earned her Master of Divinity degree from Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary in Berkeley, Calif., laying the foundation for her ministry of Word and Sacrament. Her academic pursuits led her to the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, where she earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree in Old Testament.

Rev. Sarras loves to teach Scripture and theology. She shared her knowledge through programs such as the Lay School of the ELCA East-Central Synod of Wisconsin, where she taught feminist, womanist and mujerista theology. She expanded her horizons by teaching courses such as “Introduction to Feminist Theology” and “An Introduction to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam” in Marathon County, Wis., through the Extension program at University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Rev. Sarras’ scholarly contributions challenge traditional biblical commentaries and offer fresh perspectives on matters of faith and society. Notable among her publications is “Jesus Was a Palestinian Jew — Not White,” which challenges traditional misconceptions about Jesus’ identity and roots. Her scholarly article “Refuting the Violent Image of God in the Book of Joshua 6-12” was anthologized in The (De)legitimization of Violence in Sacred and Human Contexts (Palgrace Macmillan, 2021), offering fresh insights into the violence depicted in the book.

Beyond academia, Rev. Sarras finds pleasure in hiking, biking, baking and immersing herself in books on politics, faith and Scripture, as well as watching documentary movies. In her roles as a pastor and as a scholar, Sarras advocates for critical thinking and encourages others to deepen their understanding of faith.

[1] Sidney H. Griffith, The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 9.

[2] Griffith, The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque, 8

[3] Ibid., 49

[4] Kenneth Cragg, The Arab Christian: A History in the Middle East (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1991), 54.