Knowing the numbers for hunger and poverty can go a long way to helping us talk about the issues accurately and craft effective, forward-looking responses. For those who share with their congregation information about hunger and poverty, these numbers can also be helpful in putting together presentations or workshops. Below, we have compiled the data from the most reliable sources we have for official numbers on poverty and hunger in the United States and around the world. You can download the slides to put directly into a presentation or use the numbers in your communications and work. You can also download the entire Power Point presentation at the link at the end.

Below, we have compiled the data from the most reliable sources we have for official numbers on poverty and hunger in the United States and around the world. You can download the slides to put directly into a presentation or use the numbers in your communications and work. You can also download the entire Power Point presentation at the link at the end.

Of course, we know with the COVID-19 pandemic that many of these numbers are already out-of-date. We have some estimates of how the pandemic is impacting hunger and poverty, but no solid data has yet been published. At the end of this post, we’ll go over what we know so far about COVID’s impact. (To no one’s surprise, it’s not good.)

ELCA World Hunger relies on several sources for data:

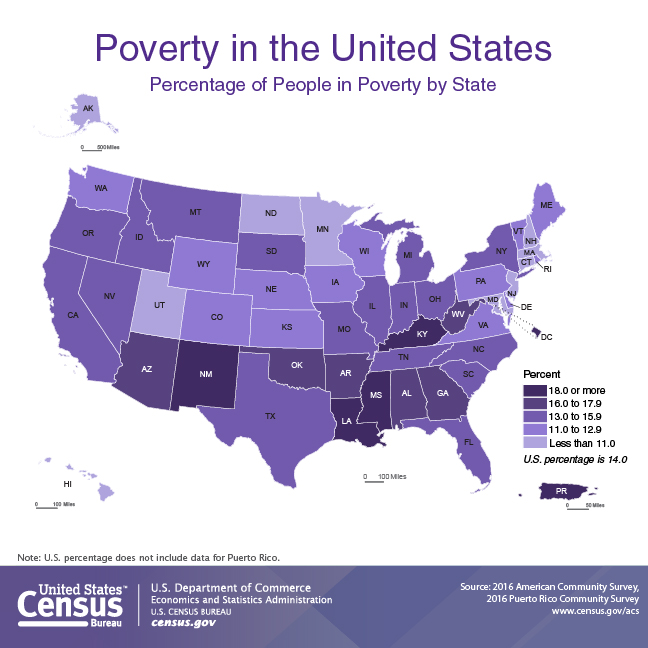

- US Poverty – the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey and Current Population Survey, compiled annually;

- US Food Security – the US Department of Agriculture’s annual “Food Security in the US” report;

- Global Hunger – the “State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World” report compiled annually by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations;

- Global Poverty – the World Bank’s reports on poverty worldwide

*One important note before we get started is that data are always for previous years. Below, we’ve indicated what years are being measured by the data. These are the most up-to-date statistics available from the sources. All statistics, graphs and charts come from the respective sources listed above.

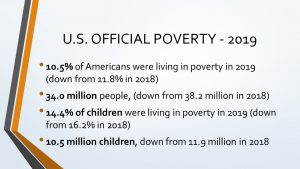

U.S. Poverty

We’ll start off with data about the United States. Here are the thresholds used to measure poverty in 2019:

The poverty thresholds are reported here as averages for households by number of people. The Census Bureau takes into account the age of householders and the number of children to determine the threshold. So, for example, for a household of four, the average poverty threshold is $26,172. The range, though, is $26,017-26,370, depending on the characteristics of the household. You can see another example in the slide under the household of a single person.

Another important point here is that the poverty thresholds differ from the poverty guidelines. The guidelines are used to determine eligibility for certain government programs, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP; formerly food stamps). The guidelines don’t vary based on age or number of children. The thresholds are used to measure poverty. The thresholds are based on three times the cost of a minimum food diet in 1963, adjusted for inflation.

To be considered “in poverty” in the US, a household’s income must be below the threshold.

To be considered eligible for some government assistance programs, a household’s income must be below (or below a certain multiple) of the poverty guideline.

One of the ongoing concerns in the US is racial disparities in poverty (as a note, these categories are the identifiers used by the US Census Bureau):

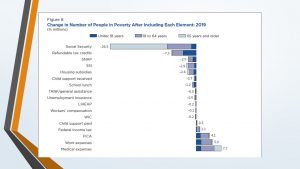

In addition to the official poverty measure, the US Census Bureau also calculates a Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM.) You can read more about the differences here, but one of the interesting things the SPM lets us see is how certain safety net programs and benefits help alleviate poverty. It also allows us to estimate how much certain costs contribute to poverty. In the chart below, we can track the change in the number of people in poverty when each element individually is included. For example, we can see in the chart that SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) helped keep about 2.5 million people out of poverty in 2019.

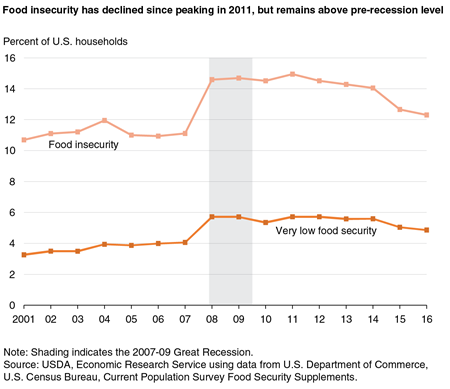

U.S. Food Security

Turning to food security in the United States, we can see a slight decrease from 2018 to 2019. The USDA uses the term “food insecurity” instead of “hunger” to capture more accurately the situation for most people in the US. Food insecurity means that at some point during the year, a household lacked access to enough food for an active, healthy life for all household members. Chronic hunger, the kind we’ll get to when we turn to global hunger, is relatively rare in the US. The phrase the USDA uses is “recurrent not chronic,” which means that households experience periods of food insecurity throughout the year, but this is usually not persistent day-to-day. For many, periods of food insecurity come at the end of the month (when benefits run out) or during seasons when work is harder to come by.

In the US in 2019, almost 11% of individuals were food-insecure. This is about 35.2 million people.

Child food insecurity in the US is really hard to measure for a couple reasons. First, children, especially young children, are usually the last people in a household to experience food insecurity. Often, adults or older children will give up their food to ensure the younger ones have enough to eat. There are also some programs specifically geared toward school-age children that can help, like the National School Breakfast and Lunch Programs. Because of the difficulty in measuring child food insecurity, the notes on the slide are carefully phrased. We can say how many children lived in households where children and adults faced food insecurity, though the data from the USDA don’t allow us to say for sure that every child in that household was food insecure.

The situation for people facing very low food security in the US is concerning. Of the 5.3 million households reporting very low food security,

- 48 percent said that an adult in the household lost weight because they couldn’t afford food;

- 36 percent said that an adult did not eat for a whole day because there wasn’t enough money for food; and

- 97 percent said that an adult had reduced the amount of food they ate because they couldn’t afford sufficient food for every household member.

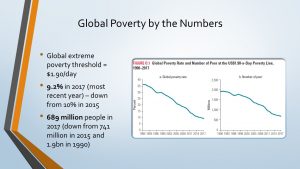

Global Poverty

Global extreme poverty is defined as income below $1.90 per day. The numbers point to some tremendous progress since 1990, when about 35 percent of people worldwide were experiencing extreme poverty. The biggest contributor to this decline, according to the World Bank, has been economic growth, particularly in Asia.

This does tend to miss another trend in global poverty, though. Fewer and fewer people are living today in what might be called “low-income” countries. What this means is that there needs to be more of an emphasis on poverty within middle- and high-income countries. Because of this, the World Bank has started measuring poverty at higher levels, since participation in a labor market in a middle-income or high-income is more expensive than in a low-income country. The general decline in the graphs also doesn’t clearly show that progress against poverty worldwide has been slowing in the last few years. Keeping the decline from leveling out will take more investment and more concerted, coordinated efforts.

Global Hunger

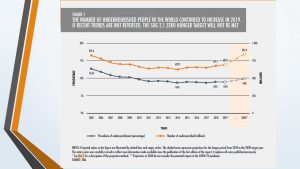

While poverty has declined, the same can’t be said for hunger. (We’ll get to how COVID-19 has made this even more troublesome later.) The most recent data we have is from 2019, so this doesn’t include the impact of the pandemic yet.

The rate of undernourishment globally has remained pretty stable since 2014. Before then, the world made some good progress, bringing the rate of undernourishment down from over 12% in 2005 to less than 9% in 2014. But in the last 5 years, the rate has crept up from 8.6% to 8.9%, or about 687.8 million people.

This slowed progress means, sadly, that we are no longer on track to meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal of ending hunger.

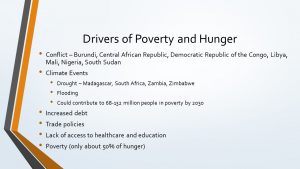

The next slide shows some of the key drivers of hunger and poverty around the world. Some of the biggest causes are conflict and climate change. Climate change, for instance, is expected to drive 68-132 million people into poverty over the next ten years. (See this earlier post for a discussion of some of the ways climate change causes hunger.)

One of the interesting things the World Bank found in its research is the complexity of vulnerability to climate events. People living in poverty are not necessarily more likely to experience major climate events, but they are less likely to have the resources needed for resilience. They are more likely to have lower quality housing, more likely to be dependent on fragile infrastructure (such as unpaved roads), more vulnerable to food price increases, more dependent on agriculture and so on. So, people in poverty will not necessarily experience more climate events, but they will be more vulnerable to the short- and long-term consequences of them.

Just one note here on trade policies. Policies that protect local producers are important to ensure a fair marketplace. But these policies also tend to protect crops such as cereals and grains. This can lead to a dearth of affordable nutrient-rich vegetables, fruits and higher-quality starches. Remember, undernourishment is not just about how many calories we consume but what kinds of calories we can access. Trade policies can play a critical role in this, both for the better and the worse.

COVID-19 Impacts

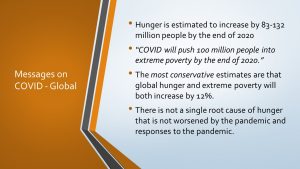

Global Impacts

There is no way of sugar-coating this. COVID-19 is causing hunger and poverty to rise at an incredible pace. The problem isn’t just how many people are affected but how quickly we were affected and how many industries were impacted.

One thing to remember is that these are estimates. We have not yet received reliable numbers, so these are projections. They’re very solid projections, but they are still just projections. Another thing to keep in mind is that, while news media may report these estimates under the collective term “hunger,” the organizations creating these estimates aren’t always talking about the same thing. There have also been big problems with collecting data, obviously.

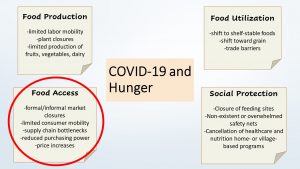

Let’s start with how COVID-19 impacts hunger. There are four big categories of impacts.

Let’s start with how COVID-19 impacts hunger. There are four big categories of impacts.

First, food production. Agriculture and food processing require a lot of human labor. With limited mobility, workers aren’t able to get to work. If they get sick, they can’t work. Plants may shut down, too, so there is a shortage of pathways for getting food from farms to tables and stores. The International Food Policy Research Institute notes that people in poverty are most affected in this category because they are dependent on their labor for income. When they can’t work, they don’t get paid.

Next, food utilization. This has eased a bit over the last year, but with trade barriers in place to prevent the spread of COVID, countries that are dependent on exports from other countries can’t get the food they need for markets. With hoarding of food, there is also a shift toward shelf-stable goods, which are not always the healthiest.

Third is food access, and this is the category that is hardest hit. Markets have closed, we’ve seen supply chain bottlenecks, and consumers have less money to spend. We saw this in the US last year, when processing plant closures led to bottlenecks that created shortages of chicken and beef in stores. There was plenty of meat being produced, but it couldn’t get to markets where we could buy it. We’ve also seen some concerning increases in food prices over the last year. That’s good for some farmers, but not great news for most folks around the world, whose income leaves them very sensitive to changes in food prices.

Last, social protection. As of last Fall, 73 countries had postponed elections or referendums, which makes them socially vulnerable. Also, many countries lack robust social safety nets, so there aren’t protections to help people weather the economic risks of the pandemic. And, of course, the pandemic has closed feeding sites and has forced healthcare programs to shift from nutrition and other priorities to COVID response. We have to remember that even as we deal with COVID, problems like waterborne illnesses, HIV/AIDS, and malaria are still significant issues.

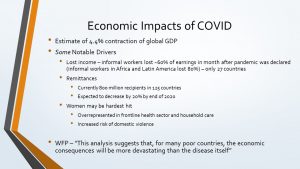

The economic impact is expected to be severe, though it won’t be equally felt by everyone.

The World Bank estimated that in 2020, COVID would cause a contraction of about 4.4% of global GDP. The consequences are widespread, too. Informal workers, especially, have been hard hit by lost income. Remittances, monies that are sent from workers in one country to families or dependents in their home countries, are down significantly. These were expected to decrease by about 20% in 2020. Women worldwide may be the hardest hit group, because they tend to be overrepresented in particularly vulnerable occupations, such as healthcare and home care, and because they face an added risk of violence at home during shutdowns. One note is worth making here. The World Food Programme’s observation about the economic conseuqneces being more severe than the disease itself is included on the slide. But it is important to remember that these impacts are being measured with the restrictive measures put in place to slow the pandemic in mind. Without these restrictions, the disease itself would also have severe impacts, including much wider loss of life.

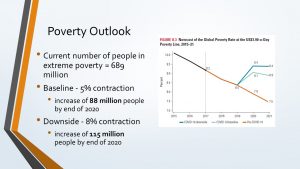

All this combines to make some pretty stark projections for poverty worldwide.

The current number of people living in poverty is 689 million. If global GDP contracts by 5%, then an additional 88 million people will have been added to that number by the end of 2020. If global GDP contracts by 8% (the high end of estimates), then we will be looking at an increase of 115 million, or a total of 804 million people in poverty. Remember, these were estimates for the end of 2020. With the pandemic still raging into 2021, these projections may be worse now, and in fact, some data suggest that global GDP already contracted by more than 5% by the end of last year.

Now to hunger. Last year, there were two estimates floating around that seem to have caused some confusion. Back in April 2020, the World Food Programme (WFP) announced that the number of people facing hunger could double by the end of the year, to 265 million.

“But, wait!” you might say, “I thought the number of hungry people was almost 690 million.” What the WFP was referring to is the number of people facing what is called “crisis-level hunger,” based on a classification called IPC/CH Phase 3. This is, as the term implies, a short-term crisis of hunger, not the long-term undernourishment we refer to typically as “hunger.” The estimate is based on the number of people who are vulnerable to a crisis (in the earlier phase of IPC/CH) falling into crisis-level hunger in 2020.

An estimate that more closely tracks with what we have been calling “hunger” is the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ (FAO) estimate of 83 to 132 million people. This maps to the statistic that ELCA World Hunger and other organizations use to refer to “people who are hungry,” namely the number of people who are undernourished.

So, the 265 million people from the WFP’s estimate could become part of the population that is chronically undernourished, but the two estimates refer to different things. The most consistent way to talk about COVID’s impact on hunger, then, would be to say that the number of people who are chronically undernourished could have grown by 83 to 132 million by the end of 2020, while as many as 265 million more people could be facing a hunger crisis. We’ll need to wait for new data later this year to see how close the estimates were.

The key point here is that the most conservative estimate was that both hunger and poverty each grew by about 12 percent in the last year. That is a staggering number.

And, as the slide mentions, there is not a single root cause of hunger that is not untouched by the pandemic, from employment to health care to food access to climate change. Everything is affected.

Domestic United States

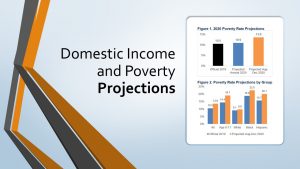

The news for the US isn’t much better, though federal legislation (through the CARES Act, the HEROES Act and the COVID relief included in the spending reauthorization bill) have masked some of the possible effects of the pandemic. Using Census data on poverty and income, the US Department of Health and Human Services estimated in October that poverty would grow to 10.9% by the end of the year, with a big jump in the Fall and early Winter. As you can see in the slide, though, the rates and estimates reflect what we already know about racial disparities in poverty in the US:

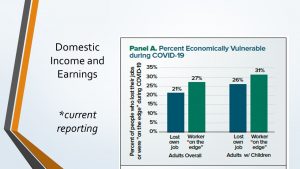

The Food Research and Action Center (FRAC) did an analysis of economic vulnerability that was really disheartening. FRAC estimates that almost 50% of adults in the US either lost their own job or were “on the edge,” which means they experienced a loss of income or reduced hours, expected to lose their job, or had a household member lose their job during COVID.

So, what does this mean in the US? First, estimates suggest that domestic hunger has already doubled or tripled since the start of the pandemic. More than a quarter of US adults are economically insecure. Importantly, the social safety net – including increases to or easing restrictions of programs like SNAP and WIC, eviction moratoria, and the expansion of the school meals program for children – have been working. Sort of. They aren’t enough, and many of the programs still aren’t available to everyone. But they have helped dampen some of the effects of the pandemic. That’s important to remember. These estimates and projections are what we have with this legislation. One can only imagine what would have happened without it.

One of the most worrisome trends is in food security in the US, which has spiked incredibly since early 2020. What is very concerning here is that we may be seeing a shift from “recurrent not chronic” hunger in the US to chronic hunger for many people.

And there we have it. We are still using the data available to us last year, covering hunger and poverty from 2019, generally, but we know that the situation has dramatically worsened, even since these reports were published. In the US, vaccination has given some a measure of hope, but access to vaccines and treatments is still far below what it needs to be in many places around the world. We are far from the end in terms of the economic impact of this. We need only recall how long it took the US to recover from the Great Recession (nearly a decade). The economic impact of COVID is much broader and deeper than even this. We have a long road ahead, as a country and a world.

Sometimes, faithful hope can be like standing on the deck of a ship watching as the port gets nearer. And sometimes, faithful hope is like clinging to a float in the middle of the ocean. We need to be honest about the projections we are seeing, but in times like these, we also need to cling in hope to what we are equally assured of by faith.

We don’t need to change the story; we just need to be faithful to the story we trust in by faith. The only future that has been written in stone is a future without hunger and thirst.

We give thanks for the work that many of you are doing to address this deep, deep need, through your local ministries, advocacy, generosity and through the work we do together as ELCA World Hunger. May God continue to make a blessing of your efforts.

You can download the slides for this presentation here: ELCA World Hunger Hunger and Poverty Statistics for 2020