Nearly 500 years ago, the young monk Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to a church door in Wittenberg, Germany, and kicked off the movement that would become the Protestant Reformation. The theological disputes that followed have been well-documented over the centuries, but what the Reformation meant for the church’s witness in the midst of hunger and poverty is often forgotten. In this series leading up to October 31, 2017, we will take a deeper look at the Reformation’s importance for the church’s social ministry – and the important work to which people of faith are called by the gospel.

Nearly 500 years ago, the young monk Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to a church door in Wittenberg, Germany, and kicked off the movement that would become the Protestant Reformation. The theological disputes that followed have been well-documented over the centuries, but what the Reformation meant for the church’s witness in the midst of hunger and poverty is often forgotten. In this series leading up to October 31, 2017, we will take a deeper look at the Reformation’s importance for the church’s social ministry – and the important work to which people of faith are called by the gospel.

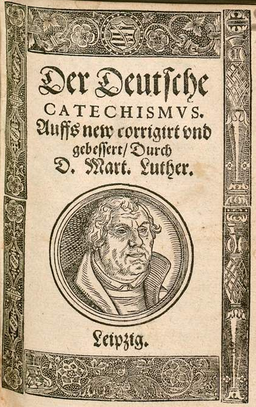

As we celebrate 500 years and look forward to the future, let’s take a look back at the past, returning to the basics with quotes from Luther’s Large Catechism. Many thanks to Samuel Torvend and Jon Pahl for their essays in The Forgotten Luther: Reclaiming the Social-Economic Dimension of the Reformation (Lutheran University Press, 2016), which superbly highlight Luther’s approach to greed and the economic dimensions of the catechisms, respectively.

#3 – “Many a person thinks he has God and everything he needs when he has money and property; in them he trusts and of them he boasts so stubbornly and securely that he cares for no one. Surely, such a man also has a god – mammon by name, that is money and possessions – on which he fixes his whole heart. It is the most common idol on earth.”

#2 – “But beware how you deal with the poor, of whom there are many now. If, when you meet a poor man who must live from hand to mouth, you act as if everyone must live by your favor…and arrogantly turn him away whom you ought to give aid…he will cry to heaven…Such a man’s sighs and cries will be no joking matter…for they will reach God, who watches over poor, sorrowful hearts, and he will not leave them unavenged.”

I wonder how things might be different if we replaced all those “Cleanliness is next to godliness” and “Jesus is my co-pilot” signs and stickers with this flashing indictment from Luther: “Beware the cries of the poor you ignore, for they will reach God.”

We’ve discussed the Lutheran Catechisms in a previous post, but here we move into a different section: Luther’s discussion of the Ten Commandments. As before, while the theological explanations that Luther offers within the catechisms are relatively more familiar to many folks, Luther adds an interesting twist when it comes to his examples of theology in practice. Overwhelmingly, his examples are economic, particularly when it comes to the 1st (“You shall have no other gods”) and 7th Commandments (“You shall not steal”), from which the above quotes are taken.

What Does This Mean?

In the 1st Commandment, Luther points out that the commandment is intended to underscore the demands of “true faith and confidence of the heart,” such that one clings to God alone. Quote #3 above is the first example Luther uses to demonstrate “failure to observe this commandment.” To have faith in something, according to Luther, is to cling to it with all your heart, to place in it all our trust, and to find consolation in naught else. The only proper object of this kind of faith is God. Theologian Paul Tillich had a great way of describing the object of faith. He called it one’s “ultimate concern.” Our ultimate concern is that object of faith which motivates our behavior, provides us with hope, and helps us understand our place in the world.

Luther saw that for many folks in his day – and, we could say, in our day, as well – the true object of faith was not God but wealth and possessions. This shaped what we might call their “active” and “passive” faith-lives. In the active faith-life, they pursued wealth, even to the detriment of other responsibilities, especially their responsibilities to their neighbors. In the passive faith-life, they rested secure in their wealth, as if they could sustain themselves with security and happiness with their possessions alone.

For Luther, this is idolatry. The active side of greed causes people to pursue wealth as if the world were merely a storehouse of possessions for them to acquire, rather than an abundant field of God’s gifts for them to steward. It also causes them to forget their dependence on God, passively resting in their own achievements as sufficient.

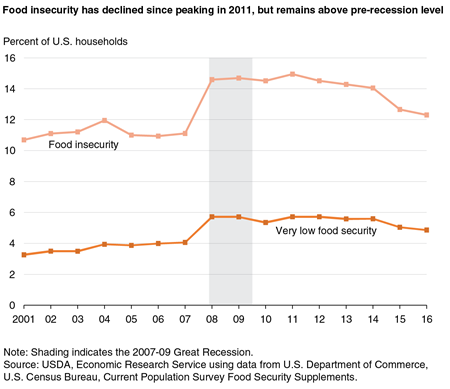

We might look at Luther’s discussion of the 7th Commandment as dealing with the first, active side of this faith, while the second, passive side is treated in his discussion of the 1st Commandment. Looking at the passive side first, putting our trust in our own wealth and possessions is a fool’s errand. Especially after the Great Recession, most of us should recognize the precariousness of wealth. Why place our trust in something so transitory? No matter how much wealth, how many possessions, we can never have the kind of “blessed assurance” that grace alone provides.

There is another insidious side to this. If we are convinced – even subconsciously – that our existence or salvation depends on our wealth, we will do anything we can to pursue it, even if it proves costly to our neighbors. This is where the active side of greed comes in, the side addressed in the 7th Commandment. In the commandment against stealing, Luther notes the more obvious violations, but then he goes in a different direction, closely critiquing economic practices that harmed people in poverty , particularly in the marketplace. He writes,

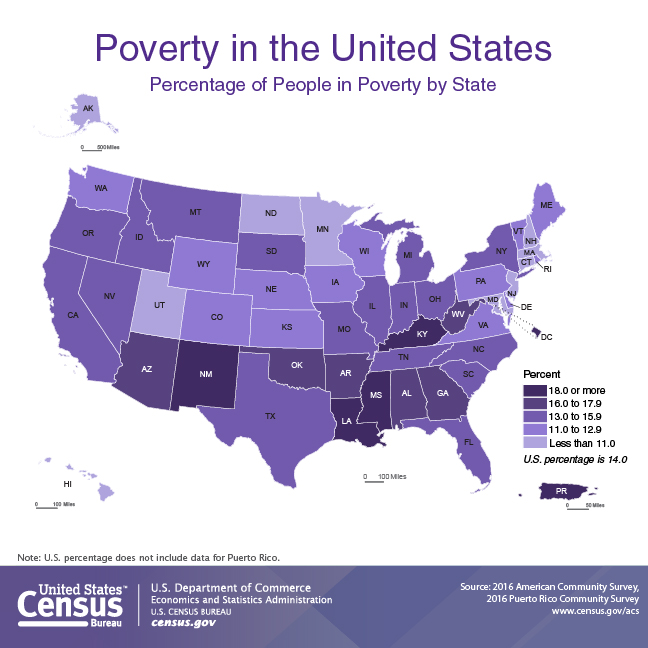

Daily the poor are defrauded. New burdens and high prices are imposed. Everyone misuses the market in his own willful, conceited, arrogant way, as if it were his right and privilege to sell his goods as dearly as he pleases without a word of criticism.

Luther was not necessarily opposed to the market or to the emerging capitalism in his day. But he was concerned that the market was providing legitimacy to the practices of greed. He took issue with the “gentleman swindlers,” who “sit in office chairs and are called great lords and honorable, good citizens, and yet with a great show of legality rob and steal.” For Luther, idolatrous greed was at the root of unjust economic practices that left people mired in poverty throughout Germany. Indeed, he called for government regulation of the economy, writing that “[princes and magistrates] should be alert and resolute enough to establish and maintain order in all areas of trade and commerce in order that the poor may not be burdened and oppressed…”

Thus, Luther saw the two commandments tied together. The idolatry of wealth led to the sin of theft; the sin of theft revealed the idolatry of wealth. True faith, then, is tied closely to economic justice.

So, what?

Faith is not a private devotion, or merely intellectual assent to a set of beliefs. Faith is a living, breathing, life-shaping reality moving within us. If our faith is something we can set aside as we enter other spheres of life, as we move from pew to home to voting booth to office. Uncovering our faith, our “ultimate concern,” means closely examining how our faith shapes our daily practices, especially, for Luther, our economic practices. Economic injustice is not merely a sin of greed but rather a revelation of idolatry, if we are taking Luther seriously. True faith moves us into deeper relationships with our neighbors, not competition against them.

What is particularly interesting is that these teachings don’t come in some minor treatise on the economy and money, but rather right smack in the Large Catechism, the very instructional guide for the faith that Luther believed should be read “daily” by Christians. Contrary to what so many generations of Lutherans since have said, there is a clear and undeniable link between faith and justice here. Idolatry leads to unjust practices; true faith leads to just practices.

With this, we can start to get a better perspective on the Reformation and why it continues to be so important. This movement begun 500 years and one day ago was not merely an internal debate about theology but a protest against the economic injustice bred by idolatrous theology. For Luther, if faith is to mean anything, it must have meaning not only within the church, but within the home, within the public square, and yes, within the market. The Reformation, perhaps, was not just about crafting a more accurate theology but also about participating in God’s building of a more just world.

499 years and 364 days later, how are we doing?