Since 2015, undernourishment around the world has been on the rise, after years of decline. In the latest estimates from the United Nations, more than 820 million people are undernourished. Even as we face the clear and present threat of coronavirus, we need to remain aware of the ongoing, persistent threat of hunger around the world. The current pandemic is revealing and exacerbating long-standing disparities – in income, access to health care, and social mobility. As the disease continues to spread, and as governments take steps to avert it, what might be the consequences for hunger?

Here are some of the things to keep an eye on when it comes to hunger in a pandemic.

Food Prices

What do we know?

One of the reasons we have seen rises in hunger in the last 10-15 years is volatility in food prices. In 2007-2008, for example, prices for wheat, corn and rice reached new highs. Milk and meat also spiked. This increased vulnerability to hunger in many countries. Some countries were harder hit than others. India, for example, saw an increase in wasting (low weight for height) among children. Fourteen African countries also experienced civil unrest over high prices, as did Bangladesh and Haiti. The research suggests that the biggest impacts of the price crisis were felt particularly among low-income groups. Some analysts also argue that the food price crisis may have contributed to the Arab Spring protests that erupted in the early 2010s.

What should we be watching?

One of the main concerns about COVID-19 early on was that both the disease and the government responses to it may cause a spike in food prices. This could be the result of infections preventing people from working in agriculture or in processing, restrictions on trade, and stockpiling[1] of food, all of which can reduce supply. As supply decreases and demand increases, of course, prices rise. If this were to happen in the midst of a pandemic, when many folks are also vulnerable to infections that can keep them from working, we might see a spike in global hunger, especially for those whose income leaves them vulnerable already. At particular risk are farmworkers, particularly field workers, many of whom are at increased risk of infection because of a lack of sufficient protocols for safety. As the agricultural industry is impacted, many of these workers may face reduced pay or reduced opportunities for work, both of which can leave them vulnerable to poverty, hunger and increased infection, especially as they pursue work in unsafe settings or under-regulated industries.

What are we seeing so far?

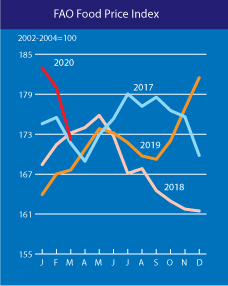

There’s good news and bad news. We aren’t yet seeing spikes in food prices. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) tracks food prices by month, and the latest data for March 2020 didn’t show significant increases. That’s good news. Also, this year is looking to be strong for harvests of wheat and some other cereals. That’s also good news. The price spikes earlier this century were often accompanied by droughts that caused down years for crops. So far, that isn’t the case in 2020. The biggest concern for now is that restrictions on trade and mobility might create a situation friendly to higher prices.

There’s good news and bad news. We aren’t yet seeing spikes in food prices. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) tracks food prices by month, and the latest data for March 2020 didn’t show significant increases. That’s good news. Also, this year is looking to be strong for harvests of wheat and some other cereals. That’s also good news. The price spikes earlier this century were often accompanied by droughts that caused down years for crops. So far, that isn’t the case in 2020. The biggest concern for now is that restrictions on trade and mobility might create a situation friendly to higher prices.

The bad news is actually in the other direction, with prices falling. In the US, many farmers rely on restaurants and stores to purchase their produce. With the closures of these businesses and direct-to-consumer markets, farmers face a challenging environment for selling their crops. The CARES Act included an allocation of $9.5 billion to help support them through the USDA.

Farmers in other countries face similar challenges. With markets closed or closing and developed economies slowed or retreating, prices for exports and commodities are moving down. This could create long-term problems for people in agriculture. In developing countries, where the share of the labor force dependent on agriculture can reach well above 50%, this is a significant problem. See below for more on exports this year.

Health Care Costs

What do we know?

Medical out-of-pocket costs are a significant driver of poverty in the United States. According to the US Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure, medical out-of-pocket costs were responsible for adding about 8 million people to the number of people living in poverty in 2018. Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank estimated that in 2010, 800 million people spent 10% of their household budget on health care, and about 100 million people were pushed into extreme poverty because of health care costs. For many, the choice to seek medical treatment is a choice between paying for care and paying for other needs, such as food.

The relationship between health and hunger is kind of a double-edged sword. On the one hand, malnutrition can lead to significant health problems, such as hypertension, anemia, coronary heart disease, and diabetes. Based on what we know so far about COVID-19, this leaves people who are hungry at greater risk of severe symptoms from infection. As people get sick, they are more likely to miss out on income and thus less able to afford food and other necessities. When they aren’t getting enough food, they are more likely to get sick. It’s a vicious cycle.

What should we be watching?

Without access to a sufficient, stable healthy diet, people who are already vulnerable to poor health will be at heightened risk from COVID-19. Moreover, in many areas, communities with high rates of poverty and hunger also have limited access to health services, particularly the kinds of specialized services that are needed to treat severe symptoms of COVID-19.

One of the ways to measure access to health care services – and along with that, the ability of a country to mitigate a pandemic – is the number of health care professionals within an area. In developed countries, the number of medical doctors per 10,000 people can be as high as 20-40. The number of medical doctors in developing countries can be lower than one per 10,000 people. Disparities exist within other needed professions, as well, such as pharmaceutical personnel and nursing and midwifery personnel. The combination of undernourishment, low numbers of medical workers and a severe pandemic is a serious problem.

The other concern is that even if they have access, people living on the edge of extreme poverty may not be able to afford health services. It’s difficult to measure the number of people who have health coverage for essential services, but based on their research, WHO and the World Bank estimate that more than half of the world’s 7.3 billion people lack this coverage. That’s a lot of out-of-pocket expenses for many of the people who can least afford it.

For these and other reasons, ELCA Advocacy is working to ensure that the next COVID-19 funding bill in the United States includes additional funding resources in international assistance to ensure effective global responses that will protect all of us here in the United States and around the world.

What are we seeing so far?

Treatment for the kind of severe symptoms COVID-19 causes doesn’t come cheap. A 2005 study of 253 US hospitals (a bit dated, certainly) found that the average cost of mechanical ventilation for patients in intensive care was as high as $1500 per day. Without insurance, affording treatment will be out of reach for many people. According to the US Census Bureau, in 2018, more than 28 million people in the US lacked health insurance. This coverage is not evenly distributed, either. Of the wealthiest households (with incomes above $100,000 per year), less than 5% are uninsured. Of households with the lowest income (less than $25,000), more than 13% are uninsured.

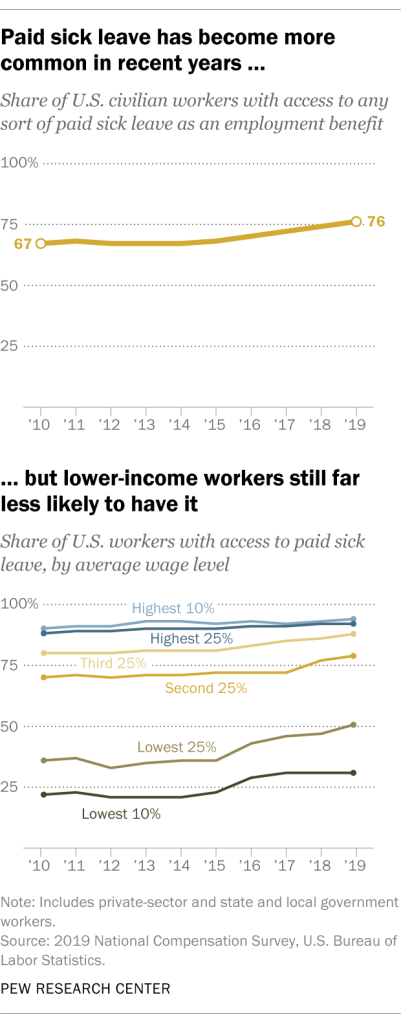

Moreover, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, more than 33 million people in the US do not have paid sick leave from work. As the Pew Research Center notes, while this has improved overall, with many workers gaining this benefit in recent years, lower-income workers are still less likely to have it. These workers are also less likely to have the financial resources to weather a major health crisis.

The long and short of it is, at this point, we don’t have a ton of verifiable data to draw conclusions about the health care impact of COVID-19 on hunger. But we do have enough information to reiterate the importance of the health projects supported by ELCA World Hunger. These projects, including hospitals and clinics, maternal and child health care, psychosocial support for mental health, vaccinations, and more, are effective ways of accompanying communities toward well-being – and building resilience to health crises. As “unprecedented” as the COVID-19 pandemic is, it is worth remembering that safety from contagious, deadly infectious diseases is not evenly shared by all. Outbreaks of Ebola, SARS, and MERS, and the ongoing pandemic of HIV/AIDS have impacted many of us and our neighbors just in the last ten years. Typically, it is the poorest households that are disproportionately impacted.

Loss of Livelihoods

What do we know?

Poverty is responsible, according to the FAO, for about half of the undernourishment around the world. Reducing poverty and achieving sufficient, sustainable livelihoods for people is critical for ending hunger. Tremendous progress has been made on this front in recent years, with poverty declining in much of the world over the last 30 years. In East Asia and the Pacific, for example, poverty has declined from about 60% in 1990 to less than 3% in 2015. Much of this decline is because of economic growth. Sadly, of course, this doesn’t mean that inequality has eased. A rising tide doesn’t necessarily lift all boats, so there is still quite a bit of poverty within countries, even as the rates overall have come down. The growth also hasn’t been even between countries. Sub-Saharan Africa has seen an increase in poverty during the overall global decrease.

What should we be watching?

The effect of sickness on income was already mentioned. But as many folks have said, the attempts to slow the virus will have their own consequences. One of the big ones will be loss of livelihoods, at least temporarily. What we are keeping an eye on here in the US is, of course, the jobs reports and the unemployment rate. Globally, we will be looking at similar things, particularly in industries like tourism, agriculture and manufacturing. In agriculture, especially, much of the work is timebound. It’s difficult to catch up on a season once it passes.

What are we seeing so far?

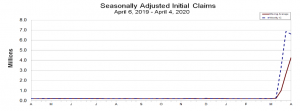

The numbers in the US aren’t good. The federal government has expanded unemployment coverage, and the number of applicants so far is astounding. According to the most recent (April 9) release of weekly unemployment claims by the US Department of Labor, more than 6.6 million people filed claims in the first week of April continuing the trend from the previous week and bringing the total number of people filing claims to more than 16 million. On a graph, the increase of late looks like a sharp right turn:

In the US, the March 2020 jobs report showed a loss of over 700,000 jobs. The biggest losses were in leisure and hospitality.

Internationally, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has reported some significant price decreases for commodities so far this year. As developed countries emerge from closures related to COVID-19, it will take some time for their economies to come back. At the same time, some developing countries are only at the beginning of the process of managing the pandemic. This could mean a long road back for exports and commodities. To put it simply, with weakened prices for exports and commodities, it may be a while before industries such as agriculture, processing and mining recover.

Social Safety Nets

What do we know?

Social safety net programs are government-funded programs that provide assistance to people during times of need. These can include benefits that allow people to buy food, cash assistance, subsidized medical care, and more. In the US, major safety net programs include the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) and others. These programs are critical supports in times of crisis.

SNAP is one of the more commonly used social safety nets. It provides people in need with money to purchase food during the month. The average benefit nationwide is about $130 per person per month. SNAP is one of the most effective social safety nets. The US Census Bureau estimates that, in 2018, SNAP helped keep about 3.2 million people out of poverty. During the Great Recession, increases to the program helped stabilize the Supplemental Poverty Measure calculated by the US Census Bureau. This helped keep people out of poverty.

What should we be watching?

Federal legislation in response to the pandemic has authorized increases in funding for some of the social safety net programs, like LIHEAP and WIC. For others, some of the requirements have been waived. For example, the CARES Act has waived the requirement for a woman to by physically present to apply for WIC. This will allow more people to apply while keeping themselves and their families healthy. The expansion of LIHEAP will help families maintain their utilities and use needed money for other necessities.

The big question right now is, will the social safety net do what it is intended do, namely prevent a short-term crisis from becoming a long-term situation of need for individuals and families?

The ELCA is working through ELCA Advocacy to encourage the US Congress to increase the maximum SNAP benefit by 15 percent during the duration of this emergency to ensure households have enough resources to avoid the hard choice of choosing between paying for their bills or for food.

What are we seeing so far?

SNAP was a big piece missing from the legislation. The Department of Agriculture, which administers SNAP, received a boost in funding, but this was not for an increase in benefits. Rather, it was to help cover the costs of what is expected to be a rise in eligible participants. So, the allocation will allow more people to participate, but it won’t necessarily provide the increased funding per person that we saw during the Great Recession. Advocating for this in future legislation is important. Again, it was SNAP increases, more than other government transfer programs, that contributed to increased jobs and reduced poverty during the recession, according to the Economic Research Service of the USDA.

Globally, the World Bank found in a 2018 study that less than 20% of people in low-income countries have access to social safety nets of any kind. Without access to public programs during crises, it is likely that COVID-19 will take a significant toll on many communities’ resilience to poverty and hunger. This will likely deepen the divide between higher-income and lower-income people within countries, as some will have the means to weather the pandemic while others may not.

The COVID-19 pandemic points to the importance of addressing hunger at the root causes. It also highlights the many ways that the burdens of crises are often not evenly shared, globally or within an individual country. The pandemic also brings into sharp relief the need for cooperation and coordination between business, nonprofits and government. Food banks and pantries have stepped up to meet immediate needs. Farmers have supported this by donating produce – at a cost to themselves. And the federal government’s legislation related to the pandemic will provide critical support.

This will be a long road, and it will require a lot of effort, particularly in advocacy with the communities most affected. To stay up-to-date on legislation and ways you can help, sign up for ELCA Advocacy action alerts at ELCA.org/advocacy/signup. In worship and in your devotions at home, remember those who are affected now and those who may be affected in the future. And stay healthy. There are many lessons for us in this situation, but one of them is clearly just how much we need one another.

[1] Stockpiling is different from “hoarding.” Stockpiling here means countries or other large entities purchasing large amounts of commodities as a security against scarcity. This isn’t the same as a shopper buying a lot of toilet paper or canned soup.