Blessings as we enter holy week! Many of you have journeyed with ELCA World Hunger through Lent as we have reflected on the Psalms and what meaning that vast collection of hymns, poems, laments and prayers might have for hunger ministry today. As the season comes to a close, thank you for being part of the 40 Days of Giving!

Lent is a common time for congregations to focus on hunger and social ministry. Indeed, almsgiving is one of the traditional “three pillars” of Lent (the other two being prayer and fasting) and is still found as one of the disciplines of Lent observed by Lutherans today. While many of us think of fasting as the core practice of Lent, the history of the church reminds us that fasting and giving are two sides of the same coin. The witness of Isaiah goes even further, describing authentic fasting as intimately tied to love and justice for the neighbor:

Is this not the fast I choose, to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? (Is. 58:6)

Scripture and tradition make a good case for focusing on hunger ministry during Lent. But this upcoming weekend may be an even more important time to reinvigorate our efforts. As pointed as Isaiah’s message about fasting may be, for Lutherans, it is the feast – and not just the fast – that calls to us.

Sharing the Feast

Say what you will about Martin Luther (no, seriously, say whatever you want – he deserves heaps of both praise and blame), but he certainly knew how to craft a pithy phrase or two. One of his most famous couplets comes from his 1520 “Treatise on Christian Liberty”:

Say what you will about Martin Luther (no, seriously, say whatever you want – he deserves heaps of both praise and blame), but he certainly knew how to craft a pithy phrase or two. One of his most famous couplets comes from his 1520 “Treatise on Christian Liberty”:

A Christian is a perfectly free lord of all, subject to none.

A Christian is a perfectly dutiful servant of all, subject to all.

As paradoxical as it might seem, what Luther is getting at is that we don’t experience God as humanity’s captor, binding us to rules and obligations, but as our liberator. That’s not to say that there aren’t obligations and demands – the Law is still the Law and still God-given. But within the Gospel, God reveals Godself to be the one who frees us from bondage to sin, death and to the notion that we can save ourselves, hence “perfectly free.”

This is a dramatic shift in Christian ethics. Why do we do “good works”? Certainly, for Lutherans, we know that those works won’t save us. No amount of fasting or almsgiving will merit a reward (or even make us good people.) And it’s not merely because the Law, with its rules for righteous living, is so compelling (we can’t fully follow it anyway.) Instead, what motivates Lutheran ethics is the experience of being loved and set free from the burden of trying – and failing – to overcome our own sin. The foundation of loving a neighbor, of striving for justice and of working to end hunger is nothing more or less than gratitude.

To play a bit with Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s popular phrase “cheap grace,” this isn’t “cheap thanks.” It’s not the kind of gratitude for all the great things we have or, worse, the gratefulness that “at least we aren’t like them.” It’s deeper than that. What moves us to choose for ourselves being “subject to all” is the realization that our entire lives, our eternal salvation, is an undeserved gift. We don’t have to worry about our own salvation, or feeling as if we aren’t enough, or fearing that the world around us will corrupt our souls or separate us from God. Instead, we can freely and boldly love and serve one another. Social ministry is not a legalistic requirement but a response to an invitation to be part of what God is doing in the world: “Come and see!”

Easter, then, isn’t the celebratory end to the sacrifice of fasting and almsgiving in Lent but the very foundation of a new life lived in gift and promise, the free gift to be bold in our love of one another and the assured promise that in so doing, we are bearing witness to God’s building of a just world where all are fed. The feast of Easter nourishes us for the work ahead.

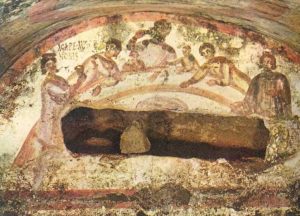

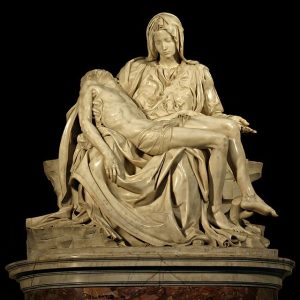

Surveying the Cross

We can’t get there too quickly, though. All too often, our Holy Week moves from Good Friday to Easter Sunday without giving us time to hang in the liminal space of Holy Saturday. Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar says that the church needs to avoid this temptation of moving too quickly from Good Friday to Easter Sunday. We have to be in that Holy Saturday moment with the disciples, von Balthasar writes, even just for a bit. For those disciples, that first day after Friday, Jesus is dead. The one they’d given up their lives to follow is now laying in a tomb. A quote often attributed to Luther describes the moment: “God’s very self lay dead in a grave.” For the disciples, there is no Easter Sunday. The messiah is dead, and hope seems lost.

We can’t get there too quickly, though. All too often, our Holy Week moves from Good Friday to Easter Sunday without giving us time to hang in the liminal space of Holy Saturday. Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar says that the church needs to avoid this temptation of moving too quickly from Good Friday to Easter Sunday. We have to be in that Holy Saturday moment with the disciples, von Balthasar writes, even just for a bit. For those disciples, that first day after Friday, Jesus is dead. The one they’d given up their lives to follow is now laying in a tomb. A quote often attributed to Luther describes the moment: “God’s very self lay dead in a grave.” For the disciples, there is no Easter Sunday. The messiah is dead, and hope seems lost.

Living after the resurrection, it’s difficult to fully understand that kind of grief, but we must because in that grief is honesty. For all the joy and hope and feasting of Easter, we live in a world where the number of people facing hunger is growing, not declining, where income inequality continues to rise, and where justice and opportunity seem further and further away, especially for communities whose strides toward progress are often stymied by violence, marginalization and oppression.

It’s a grief not only for our world, though, but also for our own shortcomings. As the church, the death of Christ reminds us of our own complicity in human suffering. Sure, the church has done some wonderful things, but the cross confronts us with the ways we have fallen short, the ways we have contributed to rather than alleviated injustice, the communities harmed by the church’s good intentions, and the people pushed aside, sometimes violently, as we have pursued what we call “mission.”

Living and Serving in Holy Week Tension

Living in Holy Saturday means living into that grief and honesty about ourselves and our world. Where Easter inspires joy in God’s promise, Holy Saturday fills us with a sacred longing for that same promise. In Easter, we celebrate it. In Holy Saturday, we yearn for it.

That movement between celebration and yearning, between joy and grief is the tension that grounds our work together as ELCA World Hunger and as a church accompanying neighbors in need. We are caught between the cross and the empty tomb, embodying the grief and longing of a long Holy Saturday before we see the promise fulfilled. And we should be. We celebrate as God works through communities near and far to create new opportunities for abundant life through neighbors joining together with determination and hope. And we lament for a world where the crosses of injustice, violence, marginalization, inequity, racism, heterosexism, sexism, ableism, ethnocentrism, exploitation and more continue to dot the landscape.

This is where the ministry of the church in a hungry world begins. Not in the self-sacrifice of Lent but in in grief and joy, in lament and hope, in yearning and thanksgiving, in the tension between Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday. It’s a costly faith that we find there, with no easy answers – but with the assurance that even then, God is still at work.

What might that mean for our day-to-day responses to hunger? What might it look like for hunger ministry to be grounded in both hope and lament? As we emerge into the season of Easter, I pray that that those questions can stay with us, that we can carry a bit of both Easter Sunday and Holy Saturday with us into the rest of the year.

Our journey through Lent doesn’t end at the cross or even the empty tomb but continues in the long walk with one another toward the future that is both promised and deeply, deeply needed.

Ryan P. Cumming, Ph.D., is the interim director for education and networks for the Building Resilient Communities team.