It’s no exaggeration to say that observing the festivals and commemorations of saints is an uncommon practice in Lutheran churches. Indeed, a simple Google search for “Lutheran AND saints” returns a wide spread of opinions, ranging from blog posts honoring particular exemplars of faith to lengthy diatribes railing against “the cult of saints.” Commemorations are sometimes controversial in Lutheranism, though, really, they ought not to be. Lutherans believe that we can honor saints by giving thanks for them and by imitating the example they have set in both faith and life.[1] Lutherans may not pray to saints or ask saints to intercede for us, but we still lift them up as examples of what it means to be a person of faith in the world.

I mention this because this month, we commemorate two particularly inspirational Catholic saints, Martin de Porres on November 3, and Elizabeth of Hungary[2] on November 17, who each exemplified “faith active in love” in important ways. What might we learn from these important leaders?

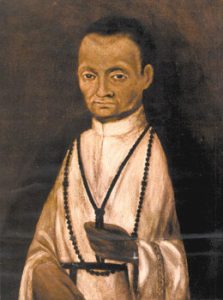

Martin de Porres

Martin and Elizabeth lived 300 years – and a world – apart. Martin was born in Lima, Peru, in 1579. His parents, a Spanish nobleman and a freed slave from Panama, were never married, and Martin’s father abandoned the family when Martin and his sister were still young. Some accounts claim that his father’s decision was due to the fact that their mother was black, and he feared the stigmatization that he and his mixed-race children would face.

The children were raised by their mother, who worked to support her children by taking in laundry. The work did not pay well, and the family grew up in poverty. At some point when he was young, Martin had to leave school and worked with a surgeon-barber in Lima, where he learned to cut hair and provide medical treatment to customers.

Martin was deeply religious and committed to helping others. Even amid his own poverty as a child, he would often give what little he had to people begging in the streets of Lima. When he was a young teenager (some sources say at the age of 15), Martin was taken in as a servant by the Dominican religious order. During his early years there, he earned a good amount of money begging, using the money to support the charitable work of the Dominicans among people who were poor or sick.

Despite his diligent work as a servant and supporter of the religious order’s charitable endeavors, many accounts state that Martin faced ridicule and discrimination because of his racial heritage. In fact, he was initially prevented from fully joining the Dominicans because, being black, he was not allowed to do so.

Eventually, this was changed, and Martin took his vows. He was assigned to the order’s infirmary, and he became widely known for the care and concern he showed for everyone in the community, regardless of their economic situation or race. In one story of Martin, there was an epidemic in Lima that sickened several of the friars in his monastery. To prevent the spread of disease, the friars were locked away in a separate part of the building. Martin violated the rules of his order by breaking into the quarantined area to minister to the ill men. When he was caught, he asked for forgiveness , saying that he did not know that obedience took precedence over charity. After that, he was allowed to continue ministering to them.

Martin continued his work in service of people facing poverty and poor health throughout his life, including by establishing an orphanage and school in Lima. He died in 1639.

Elizabeth of Hungary

While Martin’s experiences growing up poor may have motivated his charity, this wasn’t the case for Elizabeth of Hungary. Elizabeth was born in wealth, to the king and queen of Hungary, in 1207. Like Martin, Elizabeth showed deep concern for neighbors in need and an authentic spirit of generosity from an early age. She married Louis, the landgrave of Thuringia, when she was 14, and together, the couple was known for sharing their royal wealth with people facing poverty throughout the region.

Louis died in 1227, leaving Elizabeth a widow. Inspired by St. Francis of Assisi, Elizabeth became a lay associate of the Franciscans and continued her charitable work, against the protests of her husband’s surviving family. She refused to remarry, despite the political benefits that might be gained, and used her dowry to continue supporting people in need. Her charitable actions were driven by her faith in God and in memory of her late husband, who was her partner in this work prior to his death.

Like Martin, Elizabeth devoted herself to caring for people who were sick. During a famine and epidemic in 1226, she sold her jewels and opened the royal storehouses of grain to provide for people in need. Toward the end of her life, she established the Franciscan hospital in Marburg, Germany, in 1228, and she could often be found tending to the patients at the hospital alongside the other nurses and caregivers. Elizabeth died in 1231 at the age of 24.

We don’t need to venerate Martin or Elizabeth to recognize them as exemplars of the kind of faith that moves the people of God to act in the world. Their work in caring for neighbors, particularly neighbors facing health crises, has deep roots in the work of the church, from Jesus’ loving care of people suffering from hemorrhages, injuries or leprosy, to the church’s continued support of hospitals, maternal and child health care, and clinics today.

The commemorations of Martin de Porres (November 3) and Elizabeth of Hungary (November 17) are opportunities to lift up the important role the church plays in providing health care in communities. Recognizing this aspect of who we are as people of God can help us see the work of ELCA World Hunger as part of this rich heritage.

So, this month, as we mark the memory of Martin de Porres and Elizabeth of Hungary, we pray for the many ways this work continues. Whether it is through the support of hospitals, ministries among people living with HIV and AIDS, malaria prevention projects, maternal and child health care clinics, vaccination programs or advocacy for health care support in the US and internationally, the church lives out its faith in God’s promise of health and healing for body and soul.

We may not need saints like Martin and Elizabeth to intercede for us in prayer. We may not even canonize them as “saints.” But we can still learn from their memory – from a Peruvian man who refused to let racial discrimination or poverty prevent him from caring for others, and a Hungarian widow who refused to let the comfort of wealth dampen her concern for people who were sick – about what it means to be the kind of people today who can share in the transformation God is enacting in the world.

During this month, particularly on Sundays following November 3 and 17, consider honoring the memory of Martin de Porres, Elizabeth of Hungary and all those who continue the important work of providing health care by praying together:

Gracious God, we give you thanks for the many ways you sustain your creation – for the richness of healthy food, the wisdom to treat and heal, and the workers through whose hands you care for those who are sick. We give you thanks for nurses, doctors, emergency personnel, clinic workers, community educators, therapists and all those whom you have called to the healing arts. Guide them and protect them, Lord, that they may be blessed in their work. We give you thanks for those who have devoted their lives throughout the history of your church to be examples of loving care and concern for their neighbors, especially for Martin de Porres and Elizabeth of Hungary. Let us be guided by their example, that our faith in you may move us to acts of love for others. In your holy name, we pray, Amen.

Ryan P. Cumming, Ph.D., is the program director of hunger education with ELCA World Hunger.

[1] Augsburg Confession, Article XXI. See also “Apology of the Augsburg Confession,” Article XXI.

[2] Some writers have suggested that Elizabeth might more accurately be referred to as Elizabeth of Thuringia, but here, we use her more common name.