Much ink has been spilled critiquing the difference between the simplistic act of donating to the poor and the more complex ministry of accompanying those in poverty. On the one hand, it seems a good thing to put coins in a panhandler’s cup, or donate toys to a gift drive, or pack meals to be shipped overseas. In fact, all of this has a long history within the religious tradition of almsgiving. On the other hand, a whole cadre of activists and advocates have called these acts paternalistic and tried to pull (or push) well-intentioned Christians into a ministry that is marked by interpersonal relationships rather than one-sided giving of time or treasure.

Bishop Wayne Miller (Metro Chicago Synod) attempted this in 2011, when he described a continuum of ways that the church encounters the poor. At one end is pity, which essentially views people in poverty as objects of sympathy or derision. At the other end is identification, in which we identify so closely with people in poverty that we experience their suffering as our own and seek to end it. Somewhere in the middle, we move from mere pity or charity to the beginnings of actual relationships with people in poverty, a move Bishop Miller urges the church to make.

But, really, who has time or energy for that? When our good intentions have brought us to the crossroads of service, we seem left with two choices: charity or relationships. Too often, Bishop Miller and Robert Lupton (whose Toxic Charity wasreviewed here earlier this month) remind us, we choose the former, since we don’t have the time or desire to form a relationship.

I will press Bishop Miller a bit here, though I agree with him otherwise. A relationship isn’t formed somewhere near the middle of the continuum; every interaction with the neighbor forms a relationship. The question isn’t, “Should I put money in the panhandler’s cup, or should I form a relationship with her?” The question is, “What kind of relationship am I forming in this action? How will this act shape how I view my neighbor and how my neighbor views me?” The point to consider here is not whether to form a relationship but what quality of relationship the church is forming in its service.

That the church is in the business of forming authentic relationships with people in poverty and working to end their suffering is central to who we are as people of God. There are those who disagree, claiming that active service and advocacy make the church too worldly, that the church should teach the word and sacraments and focus only on spiritual matters.

To put it bluntly, they are wrong. The Law, the prophets and the Gospel reveal that there is no greater evidence of alienation from God than unrepentant alienation from the neighbor. The two cannot be separated.

Many Lutherans are familiar with Martin Luther’s famous paradox in Freedom of the Christian: Christians are perfectly free, subject to none; Christians are perfect servants, subject to all. Understanding this contradiction requires understanding what salvation means for Lutherans. We believe that sin, in its most basic form, means being “curved inward,” so focused on our own needs and our own goodness that we can’t be there for other people. By grace, God has justified us; we don’t need to be so insular. We are “curved outward” by God’s saving action, freed to be there for the neighbor.

After all the theology, soteriology, Christology, harmatiology, and so on – after all those lofty doctrines and tenets, one thing is left: the neighbor. We are saved for the sake of the neighbor. Or, more appropriately, we are reconciled to God that we may be reconciled to the neighbor. To be in relationship with God is to be in relationship with the neighbor. To serve God is to serve the neighbor. We take joy in God by taking joy in the neighbor. We express hope in God by sharing in hope with the neighbor. We commune with God by communing with the neighbor. We neglect one relationship only at the cost of the other.

We learn what it means to be in relationships by looking closely at God’s relationship with us. The most basic shape this takes is the form of the covenant. Christian ethicist Stewart Herman contrasts covenants with contracts, another powerful image of human relationship. He notes that in a contract, we demand certain kinds of behavior from other people and leave room for penalties if the contract is violated. Once the contract term is ended, both parties walk away, hopefully satisfied. A contract is marked by calculated trust, protection against risk and impermanence.

A covenant, on the other hand, goes far beyond demanding specific behaviors. In a covenant, the hope is that each party learns to value the other. Rather than being forced or compelled to fulfill a contract, in a covenant, each party takes the risk of trusting the other and becomes vulnerable to the other. Rather than ending with a term, both covenant partners move toward a future of togetherness in which the relationship doesn’t end but is deepened and fulfilled.

God doesn’t force Israel to be faithful; God moves among the Israelites, accompanying them despite their unfaithfulness, and invites them to be part of this relationship. The people are called not merely to follow the Law but to “love God.” God doesn’t merely do things for them; God loves them and claims them (Jeremiah 30:22), in a move that Bishop Miller’s “identification” recalls. More than this, according to Herman, God and Israel are vulnerable to each other. God needs Israel to fulfill God’s plan; Israel needs God to bring the plan to full flower. They depend on one another.

So much charity seems like a contract. Those with resources share them with the expectation that those who receive charity will be deserving and grateful. One party receives resources, the other receives the rewarding feeling of having done some good. Not only is this often based on distrust (“How do we know they are really poor and not scammers?” so many ask), but in some ways it depends on there being a steady supply of people in poverty to serve as contract partners. Otherwise, how would people with resources feel the satisfaction of charity?

Seeing ministry as a covenant, though, means moving toward a future together. It means taking a risk, not only that we might be “scammed” – that’s the small risk – but that we might be called to change how we see the world and how we live within it. It means recognizing our vulnerability to each other. It means people with resources seeing themselves as equally needy and recognizing that God meets those needs through the neighbor. It means moving together toward a new future, one in which the suffering of poverty is ended and not merely “addressed.”

Above all else, it means recognizing that God has called us and claimed us for the sake of our relationship with one another. In a shared world of interdependence, we will be in relationship with each other. What has been given to us is to determine whether that relationship is a mutual, life-affirming covenant or a one-sided, termed contract. To which are we called as people of faith?

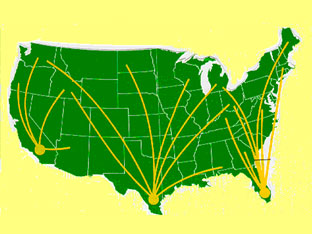

In Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies, Holmes attempts to better understand the “social and symbolic context of suffering among migrant laborers” (29). The book begins with a personal account of a dangerous border crossing, then records his work alongside a particular group of Triqui people (an indigenous group in what is now the Mexican state of Oaxaca) through harvest fields in Washington, California and back to Oaxaca. His explorations progress with the hope that his observations will help change public opinion, practices and policies (29).

In Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies, Holmes attempts to better understand the “social and symbolic context of suffering among migrant laborers” (29). The book begins with a personal account of a dangerous border crossing, then records his work alongside a particular group of Triqui people (an indigenous group in what is now the Mexican state of Oaxaca) through harvest fields in Washington, California and back to Oaxaca. His explorations progress with the hope that his observations will help change public opinion, practices and policies (29).  Map showing major migration streams in the United States.

Map showing major migration streams in the United States. Pebbles’ daughter receives SNAP benefits each month, but Pebbles herself does not because she receives a small amount of Social Security which “barely pays rent.” Getting benefits for her daughter is a burdensome process that requires “a lot of patience.” Still, she says, “I have to do it.” Without help from other family members, her daughter depends on SNAP to eat, though even with the meager benefit she receives, both Pebbles and her daughter were going hungry by the last week of each month. SNAP helped a lot, but it didn’t keep them from going hungry.

Pebbles’ daughter receives SNAP benefits each month, but Pebbles herself does not because she receives a small amount of Social Security which “barely pays rent.” Getting benefits for her daughter is a burdensome process that requires “a lot of patience.” Still, she says, “I have to do it.” Without help from other family members, her daughter depends on SNAP to eat, though even with the meager benefit she receives, both Pebbles and her daughter were going hungry by the last week of each month. SNAP helped a lot, but it didn’t keep them from going hungry.