February 2014

“Is this not the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin?”

Isaiah 58:6-7

During the first week of the meeting of the parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in Warsaw last November, a delegate from the Philippines announced that he would be fasting for the duration of the meeting to call attention to the needs of those most vulnerable to climate change. This included the people of his own country, which had just been hit by the strongest typhoon ever recorded, causing massive losses of life and livelihood. Yeb Sano’s fast caught the attention of many of the people of faith attending the meeting — fasting is a practice that people of faith understand and connect to — and a number of the young adults who were part of The Lutheran World Federation’s delegation decided to join in the fast. Their gesture of support for the Philippines spread to others in the building, and by the time I arrived for the meeting’s second week, those who were fasting could be recognized by the red fabric dots they wore on their lapels as they hurried to plenary sessions and workshops.

Following the close of the meeting, the Lutheran World Federation delegates and others decided to continue their fast, selecting one day to fast each month until the next UN meeting in Lima, Peru, in December 2014. Their hope is that people will join the fast and tell friends and family that they are doing it to call attention to the need for global action and commitment to combat climate change. The UN process is working toward a new global agreement that would be signed in 2015 and take effect in 2020.

As I noted in my reflection post-Warsaw, what our neighbors need most from each of us is solidarity. They need our commitment to act and to urge our leaders to act to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide and other gases that are causing climate change. Fasting is a practice with deep roots in many religious traditions. However, an outside observer may not easily connect a fast from food with the very real difficulties faced by communities suffering from climate change, although food security and hunger are significant consequences of changing weather patterns.

A fast from food shows solidarity with those suffering from a changing climate, but doesn’t address the root causes of climate change. A fast from activities that contribute to carbon pollution highlights the fossil fuels that are at the heart of the problem and sends a strong message about the urgent need for individual and collective action. It also helps to name the responsibility that each of us bears for a global problem. But a carbon fast is challenging in ways that a food fast is not: refraining from eating for a day or a week is possible, but it is impossible to completely eliminate activities that involve using energy from fossil fuels. In recent years, a number of faith organizations have sponsored carbon fasts for Lent, with guides on what to give up (or stop doing) and why, but none of them suggests that completely cutting carbon emissions is a practical thing to do, or even a possibility.

So both types of fasting are flawed, but both are helpful tools for calling attention to the issue of climate change.

Which fast will you choose?

Sign up for daily emails during Lent to support your fast from the Massachusetts Conference of the United Church of Christhere.

Do you have questions or want to learn more about ELCA Advocacy? Visit our ELCA Advocacy News and Updates page or contact us at washingtonoffice@elca.org.

In Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies, Holmes attempts to better understand the “social and symbolic context of suffering among migrant laborers” (29). The book begins with a personal account of a dangerous border crossing, then records his work alongside a particular group of Triqui people (an indigenous group in what is now the Mexican state of Oaxaca) through harvest fields in Washington, California and back to Oaxaca. His explorations progress with the hope that his observations will help change public opinion, practices and policies (29).

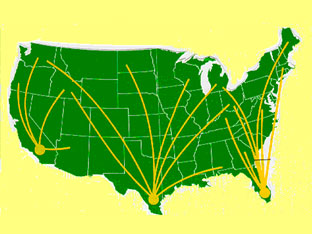

In Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies, Holmes attempts to better understand the “social and symbolic context of suffering among migrant laborers” (29). The book begins with a personal account of a dangerous border crossing, then records his work alongside a particular group of Triqui people (an indigenous group in what is now the Mexican state of Oaxaca) through harvest fields in Washington, California and back to Oaxaca. His explorations progress with the hope that his observations will help change public opinion, practices and policies (29).  Map showing major migration streams in the United States.

Map showing major migration streams in the United States.